China Has a Grand Strategy — They Want to Be the Greatest World Power

China Has a Grand Strategy — They Want to Be the Greatest World Power

Next week, the Chinese government will host 28 heads of state, as well as many senior government and NGO officials, at the 2017 “Belt and Road Forum.” Western countries will be underrepresented; the only Western head of state present will be Italy’s Prime Minister. Vladimir Putin will be there, as will Christine Lagarde, head of the International Monetary Fund. In spite of the thin presence from the developed West, the event will be a international shindig of major proportions.

The Forum is promoting a grand economic and geostrategic initiative first announced by President Xi Jinping in 2013. Informally called “One Belt, One Road,” or OBOR, it’s designated more formally as “the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road.”

What is OBOR?

Here’s a brief outline of the initiative.

In essence, as its full name implies, OBOR is designed to resurrect the Silk Road. That ancient trade route linked China and the West during China’s historical periods of preeminent wealth, power, and technological sophistication, and allowed Chinese inventions such as silk, paper, and gunpowder to reach Europe. The invocation of a glorious past is a common political strategy among countries who hope to regain those glories. We have chronicled many aspects of China’s rising geopolitical and economic ambitions over the past decades, and OBOR fits well with them.

The goal of OBOR is twofold. The “belt” will be a belt of new infrastructure — rail, road, energy, and telecommunications — built out westward into Central and West Asia, and from there, to Europe. The “road” will be maritime — new ports, shipping routes, and if early signs are accurate, naval bases — linking China more deeply with Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

Source: China Investment Research

China has said that it intends to sink a trillion dollars in the strategy. What does it hope to achieve?

China’s OBOR Goals

OBOR is focused on addressing two of the Chinese government’s existential concerns: one focused inward, the other outward.

The outward focus is more apparent: obviously, OBOR is intended to boost China’s regional power. As a very public display of ambition, it may indicate that the Chinese leadership believes that the time has come for the fulfillment of a dictum of Deng Xiaoping, the leader who opened China in the 1980s and set it on its current development path. Deng famously said, “Hide your strength and bide your time.” Xi Jinping clearly believes that China’s time has come.

OBOR will secure and expand China’s regional leadership by tying lesser-developed regional powers more deeply to Chinese capital, Chinese markets, and Chinese infrastructure networks. Indeed, China has been pursuing this kind of “soft power” for some time; we’ve written about how China has ingratiated itself with various African governments by providing infrastructure capital when Western lenders were more reticent. This year we got the first evidence of what usually follows “soft power” as China began construction of its first foreign military base, in Djibouti. Not surprisingly, this base is near the strategically critical Mandeb Strait between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, one of the eight global chokepoints for seaborne crude oil shipments.

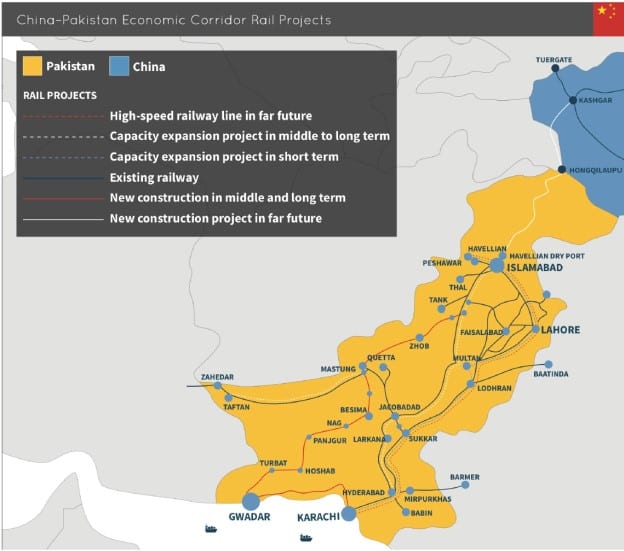

Other energy and port infrastructure tied to OBOR also aims to reduce China’s vulnerability to energy shipment disruptions by building pipelines to bypass the Strait of Malacca. This is one of the main potential benefits of one of OBOR’s flagship programs, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, or CPEC, which will involve major development of the Pakistani port of Gwadar and could ultimately serve as an energy transshipment point.

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: A Major OBOR Initiative Tying China’s West to South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa

Source: Government of Pakistan

Since OBOR was launched at a time when China has been expressing a more assertive regional and global presence, it is easy and natural to see OBOR through that lens. However, it’s important not to lose sight of the initiative’s core economic significance.

China Needs a New Development Phase, and Hopes OBOR Will Fit the Bill

China’s response to the 2008 global financial crisis was stimulus — a lot of stimulus. That stimulus resulted in a great expansion of productive capacity, and probably rescued China from a near-recession (not to mention Australia and other materials exporters). China’s steel production nearly doubled between 2006 and 2015, an increase in annual production in absolute terms nearly as large as the entire 2015 production of Europe, North America, and the C.I.S. (Russia and its neighbors) combined. However, much of that productive capacity is now acting as an overhang on the economy. OBOR is immediately aimed not so much at exporting Chinese goods, but at exporting that Chinese productive capacity itself — so that Chinese companies will move their lower value-added production to their less-developed neighbors. This would be offshoring, Chinese style. In the end, it would result in wealthier neighbors who, hopefully, would provide markets for Chinese higher-value-added goods.

OBOR is therefore also ultimately a way to try to deal with the high leverage created in the Chinese economy by the policy response to the global financial crisis — offering firms with excess capacity and high debt levels a possible light at the end of the tunnel. OBOR seeks to leverage the development prospects of poor countries in Asia and Africa as part of China’s own deleveraging strategy.

The Chinese Want To Sell To Their New Customers — “Chinese Equipment, Chinese Technology, Chinese Standards”

Chinese officials believe that its neighbors linked in OBOR will be more willing and better customers of higher-end Chinese industrial goods than Western countries, so OBOR is a key element of its program to move up the industrial and manufacturing value chain. High-speed rail is a key example: the Chinese are proud of their accomplishments in building out a high-speed rail system (half the world’s high-speed rail is in China), and the government is already using it in projects in Thailand, India, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Many of these projects were marketed personally by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang.

This reveals another key Chinese goal. The Chinese government believes that the ultimate key to domination in any industry is the control of standards. Beginning with high-speed rail, but also with telecom and energy transportation, OBOR is intended to put Chinese standards in place.

Further, the development of OBOR — looking largely westward as it does, to Central Asia and ultimately to Europe — is intended to bring China’s poor west into the orbit of the last two decades of economic development, which it has lagged. Xinjiang, for example, is home to ethnic Uighurs, Chinese Muslims. Xinjiang has been a source of political instability and of terrorism, and the Chinese government is convinced that poverty is the root cause.

And of course, underlying everything, as we never hesitate to point out, is the consciousness of China’s rulers that growth is their salvation from any political rebellion against their authority. Keeping the growth engine humming while deflating the economy’s debt bubble in a controlled fashion is the name of the game, and the stakes are existential.

A Bold Gamble, or a Desperate One?

As a response to many of China’s social, political, and financial stresses — and as a bid for the greater regional and global stature that China believes is its historic birthright — OBOR is a bold and grand design. Can it work?

There are some problems.

First, most of the investment it is pursuing is in countries that are poor and unstable, many of them chronically wracked by terrorism and political unrest. Many of them also have markets and economic institutions that are corrupt and opaque. There is the possibility that a lot of China’s money will be wasted, lost to graft or political turmoil. In Pakistan, for example, the high profile CPEC project was accompanied by the dedication of 12,000 Pakistani security forces to the infrastructure programs in the troubled north and in Balochistan.

Second, this risk is not lost on China’s financiers. While public capital will follow the dictates of China’s rulers, China’s private capital is more hesitant. We read many comments from Chinese banks to the effect that they would contribute only as much to OBOR projects as they are mandated to contribute — they are not sanguine about their likely losses. Two-thirds of currently envisioned OBOR projects are in sub-investment-grade economies. Also, some Chinese financial actors believe that the extension of massive credit to OBOR projects will ultimately not just fail to deflate China’s bubble: they think it might burst it.

Third, many regional powers — especially India, with whom cooperation is particularly important — are deeply suspicious of China’s motives.

And finally, we wonder whether it is really true that poverty is the decisive factor in a country’s instability or a culture’s predilection for political violence. Our observation of culture and history suggests otherwise: and in the contemporary world, terrorism has often arisen among highly affluent populations. There is a poverty of the soul for which material development cannot compensate. Many of the linchpin countries in OBOR may prove to have more intractable political problems than the Chinese government appreciates… or that Chinese capital will want to entrust itself to, absent the application of thumbscrews.

In spite of these problems, it is our view is that China will increase its influence over much of the OBOR region, and will succeed at least to some extent in making regional governments favorable to China’s goals. This will boost China’s success — economically, politically, and militarily. To say it another way, we think China will be at least partially successful in building a U.S.-style hegemony over parts of the OBOR area. In our view, such hegemony is part of their master plan to become and remain a major world power.

Investment implications: In its current phase, OBOR has few immediate direct implications for investors in the developed world. In a broader perspective, because OBOR is a critical component of China’s strategy to maintain growth and to cope with the financial and economic excesses of the post-crisis period, it’s important for investors to monitor its progress as part of monitoring the health and stability of the global economic expansion.

The failure of OBOR’s economic programs, or their very slow progress, would suggest trouble ahead for China. Their success, if vigorous, could conceivably reset expectations of an eventual Chinese financial crisis and convince global investors that China will be able to manage its deleveraging. We’re watching OBOR, and will keep you up to date with developments.