Although the news is focused on the human drama of COVID-19 — with quarantines, heroism, tragedy, and fear — economists and financial analysts are busy working through different scenarios for the impact that the epidemic will have on economic activity and economic growth, both in the most affected countries and worldwide. Of course, our thoughts and prayers go out to everyone affected by the outbreak.

Obviously the most severely affected country is China, where a great deal of manufacturing capacity has been shut down and logistics were severely disrupted by efforts to contain the virus’ spread. We can argue the merits of closed and open societies when it comes to handling this type of public health emergency, but on balance, the Chinese authorities have been competent, though heavy-handed; and some individual physicians have been heroic and self-sacrificing — including those who struggled to get officials to acknowledge the severity of the outbreak early on.

As we look at the emerging data outside China, where we are more confident in the objectivity of these data, it seems likely that COVID-19 will become globally endemic. Like the flu, it will result in annual fatalities, primarily among immunocompromised populations. In short, it will become a troublesome fact of life, but does not seem likely to become a real global “black swan” event; it is unlikely to match the severity even of such past global pandemics as the Spanish Flu of 1918 (which had a mortality rate of about 10%, versus an apparent mortality rate for COVID-19 of about 3–4%, though that number may change).

Needless to say, the state of medical science is vastly improved from a century ago. Moderna Therapeutics [NASDAQ: MRNA] has already announced a phase one clinical trial for a vaccine candidate. That is a remarkable achievement, though we stress that such early clinical trials rarely result in a marketable vaccine. Other companies, such as Gilead [NASDAQ: GILD], which has a deep pipeline of antivirals due to its leading HIV treatment franchise, are racing to develop or apply existing antivirals. That will rapidly create new treatment options and reduce the disease’s mortality still further. This is one occasion when we can stop arguing about drug pricing for a minute, and be grateful for the immensely powerful innovation engine of American biotechnology.

What About the Long View?

Therefore, although the immediate effects on the Chinese economy, and through it, on the global economy and on the revenues of some companies with high exposure to Chinese markets, may be severe, they are likely to be transient. We are more interested in the long-term trajectory of the Chinese economy and its growth. That has real implications in an emerging global order that seems to be increasingly split between the western/U.S. model — capitalism plus open societies and liberal democracy — and the Chinese model — capitalism plus a closed society and an authoritarian central government. China’s longer-term economic trajectory will have a profound impact on the appeal its model has to much of the developing world.

Will China overtake the U.S. in economic might, as many pundits and talking heads fear? We have often addressed this question, and the answer bears repeating. In GDP per capita, it is likely that 30 years from now, China will still not have overtaken the United States. Even in absolute levels of GDP, with its much greater population, it is quite possible that 30 years from now, China’s economy will, in U.S. dollar terms, still just be a fraction of the size of the U.S. economy.

For this analysis we rely on the excellent work of Jonathan Anderson at Emerging Advisors Group, who our readers will remember as the China analyst we hold in the highest regard. His argument runs something like this:

What really matters is the size of the Chinese economy in U.S. dollar terms, not adjusted for so-called “purchasing power parity” — a methodology used by some academic economists, but not really useful to those interested in a country’s geopolitical clout or in its potential market returns.

So there are three important pieces… (1) China’s real GDP growth; (2) local inflation; and (3) the exchange rate of the yuan to the U.S. dollar. In order for China’s economy to overtake the U.S. economy in absolute size, those numbers have to add up to a total that significantly outstrips the GDP growth of the U.S.

In the past, with a strong real growth, modest local inflation, and an appreciating currency, China has managed this quite well. What will change going forward?

As it turns out, almost everything.

First, real growth: in a nutshell, China’s real growth over the past 20 years was based on spectacular export growth, and explosive real estate and construction sectors. Both of those are well into the territory of diminishing returns. Export growth is challenged by the rise of regional manufacturing rivals, and the rise of Chinese wages. Property and construction growth are increasingly hampered by the extraordinary debt burdens that have arisen in the Chinese financial system as their shadow. China has largely exhausted the potential for credit-led expansion. “New economy” sectors, such as e-commerce, are remarkable, but are not really economically significant enough to take up the slack. Moving forward, it is very likely that real growth will continue to decelerate, and that it is already significantly below officially reported statistics.

The other fly in the ointment is the exchange rate.

The simple truth is that the yuan is not undervalued; it is overvalued. The dynamics of the yuan exchange rate in coming decades will probably be even more important in relative Chinese growth than the underlying real economic growth.

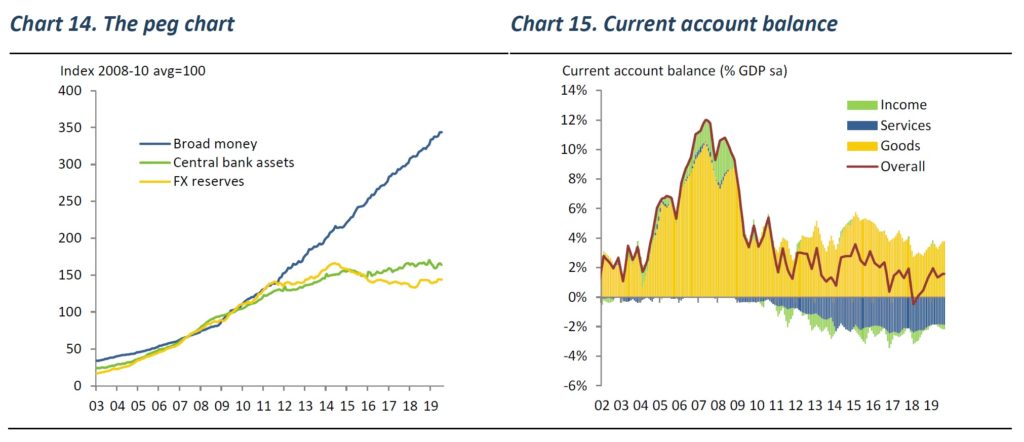

Anderson provides this graphic:

What this shows is a dramatic detachment between the total of “broad money” (M2) in China, and its coverage in foreign exchange reserves and central bank assets. In Anderson’s words, this “inexorably raises the risk of an eventual ‘run’ on the [yuan] in the form of destabilizing capital outflows… forcing the authorities into repeated rounds of devaluation in order to boost the coverage of remaining reserves or to abandon exchange rate management altogether.”

He sees this day of reckoning not in the immediate future, but in coming decades — just when conventional wisdom believes we’ll be waking up to a Chinese economy that’s overtaking the U.S.

He is at pains to point out that this is not a uniquely Chinese phenomenon — in fact, it is a common occurrence among developing countries with a currency peg; common enough almost to call “unavoidable.” Few developing countries have managed to skirt it.

In the big picture, then — far beyond the impact of COVID-19 — China is facing economic and financial processes that will put its bid to surpass the size of the U.S. economy in serious question. How it navigates the coming challenges will also have a powerful impact on the appeal of the “Chinese model” to the developing world.

Investment implications: The available data suggest that the impact of COVID-19 on the Chinese economy will be sharp, but ultimately transient. What is more ultimately important is the long-term deceleration of the Chinese economy, and the likely future exchange-rate pressures on the yuan. Those factors make a Chinese overtaking of the U.S. economy unlikely, even over the next several decades. And that in turn has implications for long-term investors who are contemplating the likely trajectory of the newly emergent bipolar global order, with capitalism ascendant, but in competing forms: democratic and authoritarian. The dynamics as they currently exist favor the former — in spite of a common wisdom that frets about Chinese supremacy.