The recession caused by the pandemic lockdowns has led to astronomical spending increases by the Federal government, and the monetization of a torrent of newly created debt by the Federal Reserve. This coordinated monetary and fiscal response sets the current crisis policy apart from what followed the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, when the monetary and fiscal responses were often at loggerheads. This is one reason that we believe the stimulus will be more immediately effective — although fraught with some potentially unpleasant long-term consequences.

Combined with the moderating and manageable character of the pandemic itself, this is our base case for a faster economic recovery. There are encouraging signs already that new business formation is up sharply, which we’ll write about next week. “Creative destruction” is at work, and its fruits will be positive for the economy and for stock market investors.

However, the lockdown recession is not affecting only Federal government finances. States and municipalities are also facing large budget holes, in many cases too large to be filled by budget cuts. The gridlock and fiercely partisan bickering at the Federal level have delayed the arrival of a new stimulus bill that would funnel aid to state and local governments. Collectively, there is expected to be a shortfall of about $200 billion for state and local finances in 2020 and 2021. (We note that shortfall is significantly less than some of the numbers being floated in the Congressional debate about the next stimulus — lending some credence to the skeptical view that some local authorities will see their shaky finances and excessive spending bailed out on the Federal taxpayer’s dime.)

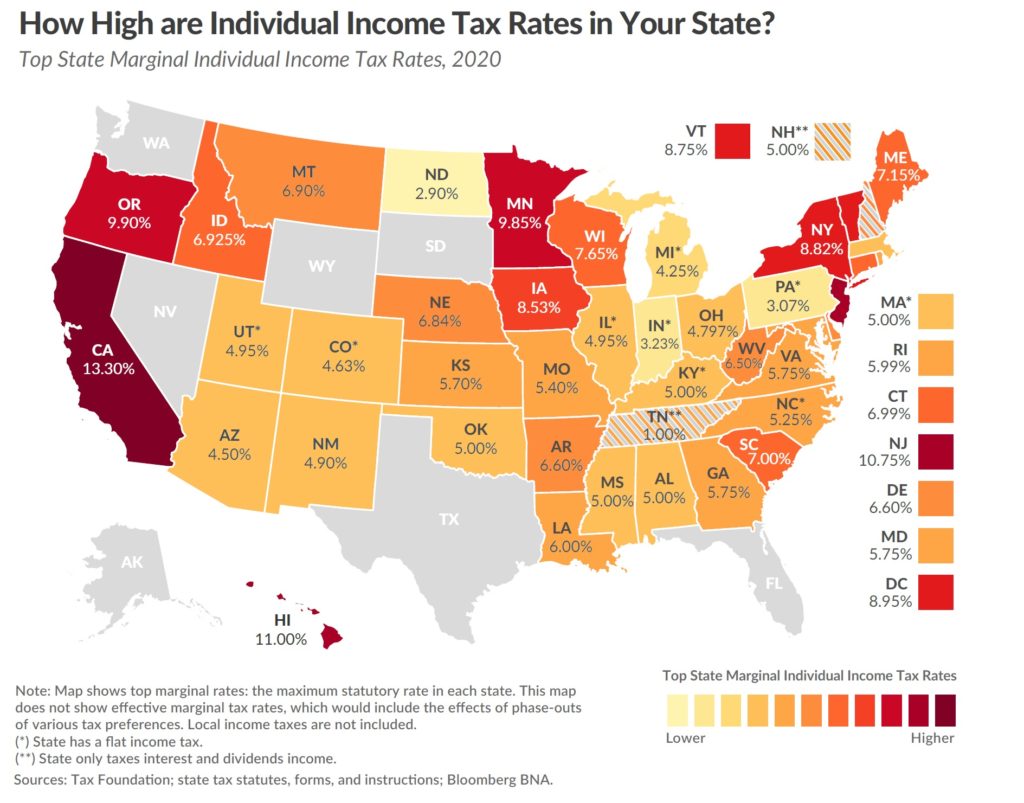

Unlike the Federal government, state and local authorities usually have to balance their budgets; so we can be sure that taxes will be rising in many places. Lawmakers in California, Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, Wisconsin, Hawaii, New York, Oklahoma, and Vermont have all proposed levying higher income taxes. More will probably follow. Municipalities, such as Chicago and New York City, are contemplating income tax hikes too, and more are preparing property tax increases. Of course, much state and local revenue comes from other incidental taxes and fees, and we can be sure that these will also be rising in many places.

Californian lawmakers are even floating a wealth tax, which we discussed a few weeks ago. Certainly such a tax — the first of its kind in the country — would be a windfall for tax attorneys and accountants (and probably a net negative for the state’s finances, if the experience of wealth taxes in Europe holds here).

Lawmakers usually suggest that increases will affect only the very wealthy, but in practice, the very wealthy on their own don’t have enough cash to satisfy the spending beast, and higher rates invariably “trickle down” to the middle class (especially as inflation pushes people up the tax brackets). Further, increases are being presented as emergency options, but government hates a sunset clause. In most cases, the “emergency” will become permanent and taxes will remain at their new, elevated levels.

As we observed a few weeks ago, these “indignities” come at a time when it has become easier than ever for the most productive and capable workers to live wherever they wish. In the past, residence has been pretty “sticky” — and there has been little migratory effect of higher taxes pushing out individuals. (Business is another story, witness the gradual 20th-century exodus of the defense and aerospace industry from California.) But now, in the era of pandemic-accelerated digitization, there may be less stickiness — particularly if the exodus from high-tax jurisdictions gains momentum, and culturally enticing pockets of well-heeled workers and businesspeople grow in more tax-friendly, low-regulation states and cities.

We think this change is already happening. The potential political effects are large. The incremental departure of the most productive and talented and ambitious creators and entrepreneurs will challenge the political programs of the high-tax, high-spending, high-regulation states, and could lead to political and cultural shifts among those economic elites themselves as they fan out across the country and find themselves in different cultural climates. Political and economic mismanagement has a cost, and despite the deep cultural capital of some high-tax citadels, they may find themselves gradually upstaged in the coming decade. This in turn could lead to political shifts and realignments on a national level.

Investment implications: The shifts described above will be of cardinal importance to real estate investors in particular. Forward-thinking and risk-taking real-estate investors would be advised to study the trajectory of tax and regulatory policy in different U.S. states.