Among many investors and analysts, there’s a growing sense that rising growth, inflation, and interest rates are bringing and end to the long “Goldilocks” phase of the bull market that began nine years ago this month. That doesn’t mean that stocks have no more gains to deliver — far from it. However, it does mean that those gains are likely to be accompanied by greater volatility. There will still be gains to make, but investors will likely need to be more nimble with market rotations between sectors and industries. They will also need to pay more attention to the strengths that differentiate superior companies from their competitors. “Goldilocks” may be passing in this sense, but the bull market isn’t over by a long stretch.

It was a “Goldilocks” period for investors, but not necessarily so much for the U.S. economy. A weak recovery, a jobless recovery, a low-growth recovery — call it what you will, it was an economically frustrating period. Some blamed the severity of the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession. Some blamed crisis policy responses that created higher taxes and more regulation. How much weight you give to each of those explanations probably depends on your political point of view.

Whatever the cause, one thing seems apparent. This period of sub-par economic performance is also reaching an end, and growth, employment, and productivity are turning the corner. This is not to say that the new higher-growth, higher-profit trend for many companies in the U.S. and worldwide will last forever, of course. But it is a shift that is now becoming apparent, and which we believe will last as long as the current cycle of expansion continues.

Last Week’s Job Report — An Important Sign

We saw a powerful sign of this accelerating expansion in the February jobs report that was published last week by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In February, U.S. employers added 313,000 jobs. Unemployment remained at a nearly two-decade low, 4.1%. Jobs increasing, and unemployment staying steady? That makes sense because of something that’s more significant: new people entering the workforce. More than 800,000 Americans did that in February — the largest one-month pop in this number since 1983.

Rising wages caused some consternation in January, stoking fears that inflation was heating up more rapidly than people thought. But wage gains for February were more muted, moving up about half as much as they did in January.

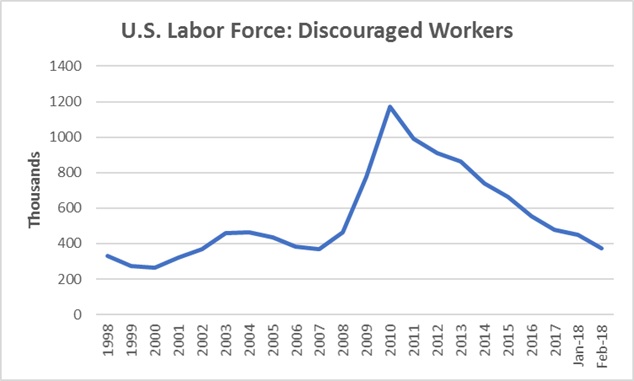

Taken together, these figures imply several things. One is that the low headline unemployment numbers may be somewhat misleading, if they’re taken to imply that the labor force is getting very tight. There’s still a fair amount of “hidden slack” among workers who had dropped out of the work force. The number of discouraged workers — those who wanted work, but couldn’t find any and quit looking — declined to 373,000 from 522,000 a year earlier, hitting a level not seen since before the Great Recession.

Data Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

An even more important implication of this strong jobs report is that the economy can continue to run strong without overheating. Inflation is tied closely to interest rates, and interest rates are the thing investors are watching nervously. February’s job numbers suggest that the economy can continue to deliver growth without creating wage-push inflation and causing interest rates to rise. Still, low- and middle-skilled workers are finally seeing their wages begin to make up some of the ground they lost over the past two decades.

Maybe rising volatility this year spells the end of a Goldilocks bull market and the arrival of more volatility. But it seems to mark the arrival of a Goldilocks phase of the economic expansion.

Investment implications: Market volatility is likely to continue this year. However, the underlying economic data aren’t alarming. On the contrary, we’re seeing job growth with strong but not excessive wage growth. We’re also seeing improving conditions for workers who have experienced a rough two decades. If this trend continues, economic strength will persist for some time, drawing discouraged and marginal workers back into the work force, before an overheating economy begins to send warning signals to the Fed that would result in rapid interest-rate increases. February’s jobs report bolsters our bullish view of U.S. economic growth, productivity growth, and corporate profit growth.