Many investors are cycle-watchers. The cycles they watch vary greatly and encompass the whole spectrum of economic, financial, political, and geopolitical events and trends. Some are brief, some are long, and some (such as the Kondratiev wave cycle) attempt to frame and track historical epochs. We do not assign decisive weight to any of these cycles or the theories that accompany them, because we have not seen that any of them in isolation — or even in some definite, reliable combination — are reliable enough to guide tactical and strategic investment decisions. In the language of science, investment markets are complex systems — too chaotic to be boiled down to a “master theory” that will allow automatic outperformance. Anyone who tells you they aren’t, is trying to sell you something. (Something you shouldn’t buy.)

Still, the cycles are worth watching — not as decisive indicators, but as part of the overall picture that artful investors create to guide their decisions. In part, this is due to the attention that other investors and market participants give to them. If enough people are paying attention, they can become self-fulfilling prophecies for as long as that attention lasts.

The “Presidential Cycle”

One of the storied cycles watched by investors is gaining the usual attention as we head into an election year. (Are there any years that aren’t election years any more? Another question for another time…) That of course is the “Presidential Cycle.” This cycle, along with many others, was first closely examined by Yale Hirsch, the creator and publisher of the Stock Trader’s Almanac. Hirsch put a number of tried-and-true aphorisms into traders’ vocabulary, including the adage to “sell in May and go away.” (Whether that one will work this year remains an open question — illustrating again how all of these cycles are statistical phenomena that are not reliable in isolation.)

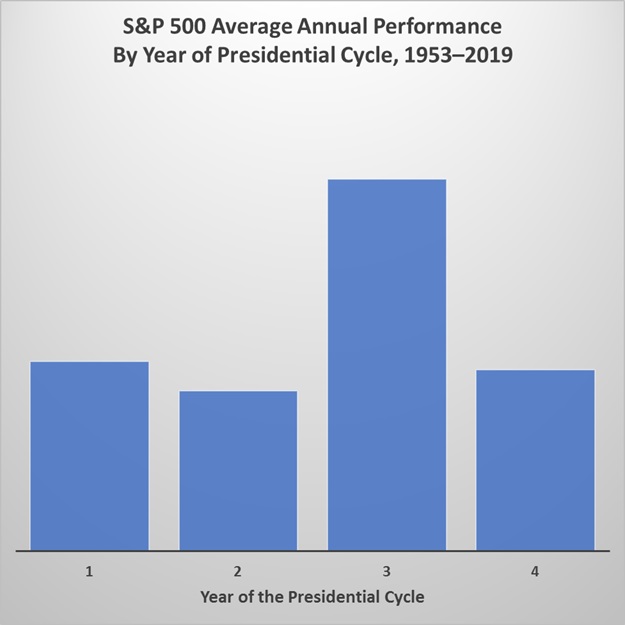

The data for the Presidential Cycle are relatively limited. We start in 1953, when Eisenhower took office, inaugurating the first real post-World War Two cycle. (The post-war transformation of the U.S. and global economies was firmly underway by this point, marking a convenient starting-point for analysis). That gives us data from ten cycles to work with, including the current incomplete cycle. That’s not a lot, but it’s enough for a pattern to emerge that makes sense.

The first and second year of a president’s term are often ones in which difficult or unpopular policies are enacted — wars are launched or economic policy reforms are made. We would expect stock market performance to be muted on average. In the third year, policies are in place and changes have been better digested; we would expect stock market performance to improve. And in the final of the four years, we would expect a certain level of distraction and concern from markets about the potential for regime change — and expect somewhat worse performance.

Indeed, that’s the way the data shake out — with all due allowance for a lot of variation given the relatively small data set.

As you can see, the performance of the S&P 500 year-to-date in 2019 is about in line with the third-year Presidential Cycle average. While, to emphasize again, there is wide variability in the historical data, these data broadly line up with our current view of U.S. market dynamics.

It’s possible to parse out this cycle in more granular detail — by political party, for example; or by re-election patterns — but given the small data set, and the endless subtleties with which it can be analyzed, we don’t think it’s wise to go overboard.

Indeed, we think it’s advisable for investors not to fixate on the Presidential Cycle. The data suggest that other political factors are ultimately more important — particularly the composition of the U.S. Congress. When it comes to the executive branch, the ultimate effects of an administration’s policy direction often don’t make it through to the economy until years after that administration has left office. The main reason to pay attention to the Presidential Cycle is simply that other market participants are paying attention to it as well.

Investment implications: The Presidential Cycle is in broad conformity with our current view of the U.S. market. Despite a variety of political and geopolitical “storms,” the U.S. market is performing about in line with what one would expect in the third year of the cycle, after a president has had the opportunity to enact some signature policies and some political dust has settled (not enough, in the current case). While the storms continue, we see the potential for further appreciation of U.S. stocks in 2019 given the signs that the U.S. and global economies are beginning to turn up from the third slowdown of the post-2009 expansion (see our Market Summary for more comments on this). Also, central bank policies worldwide remain supportive of markets and there is no sign yet that the credit cycle is nearing a turn. The Presidential Cycle is one more data point suggesting that investors would be wise to hold the course and not become prematurely pessimistic.