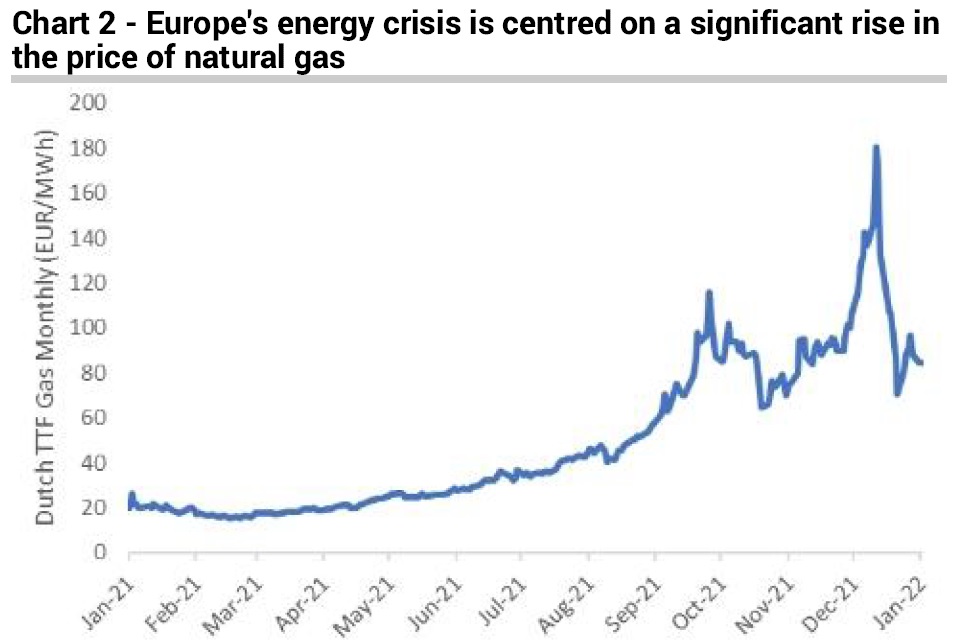

Most observers would agree that Europe’s energy sector has reached a point of crisis. Political, geopolitical, and macroeconomic trends are colliding in a volatile mix that has led to significant price volatility and public anxiety. Gas has been a key culprit.

Source: Jefferies Equity Research

The forces that are at work driving Europe’s energy prices higher include both short and long-term factors and are likely to endure for many years. Notably, the bugbear of dependence on Russia for so much of Europe’s industrial-sector energy and power-generation needs is likely to create volatility as long as relations between Russia and the west remain fraught. That looks to be the case for the foreseeable future, barring some cathartic resolution through armed conflict or regime change.

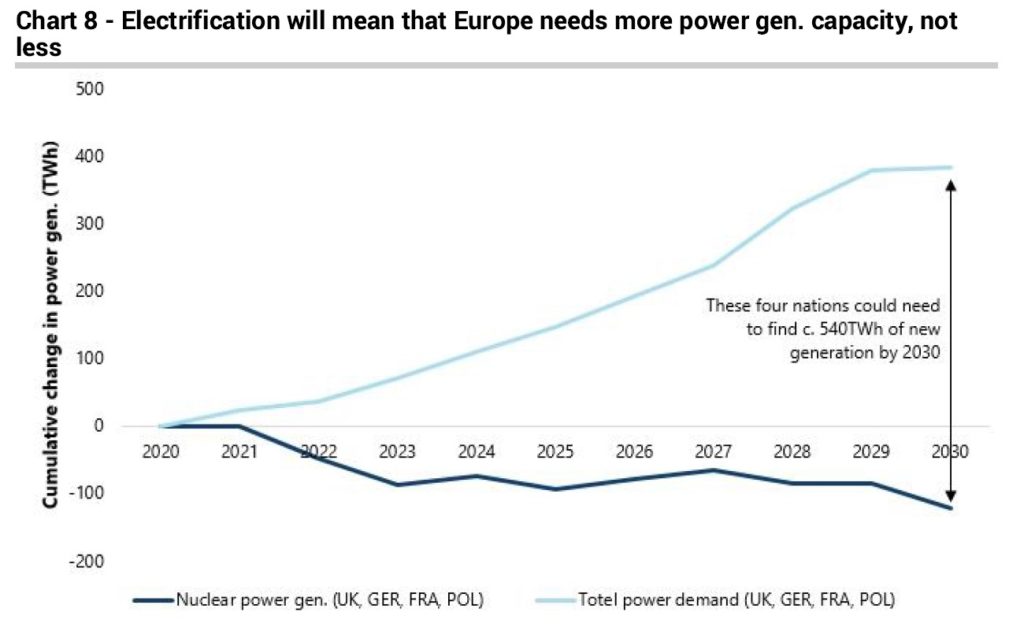

If the source of Europe’s most important carbon energy and the volatility in its price are the rock, the hard place is surely the commitment of European governments to a “sustainable” path in energy. Until recently, that notion of “sustainability” has not included the one technology that could abundantly and reliably meet the continent’s baseload generation requirements — that is, it has not included nuclear energy. Indeed, current and projected nuclear capacity has been on a sharp downward trajectory, even while the anticipated need for electric generation capacity are rising rapidly due to intended phase-outs of hydrocarbon sources.

Source: Jefferies Equity Research

Most of Europe’s nuclear powers — even France, historically friendly to nuclear — have been either aggressively (Germany) or gradually (UK, France) planning reductions in nuclear capacity in recent years. Germany is moving forward with plans to decommission its entire fleet of nuclear plants. The UK is decommissioning old plants, and cautious about plans for new ones. France committed to reduce nuclear to 50% of generation from 70%, though the topic has emerged as a contentious one in upcoming elections, with incumbent Emmanuel Macron pivoting to a pro-nuclear stance under pressure from his rivals on the right.

Why have Europeans been skeptical of the one really robust, currently deployable solution that will “square the circle” of decarbonization and abundant, reliable energy? The concerns focus around waste disposal, risks of accidents, and the protracted build periods and typically huge cost overruns of large nuclear projects.

However, we can observe two very positive trends. One is the move of EU-wide regulators to include nuclear energy in the suite of technologies that are acceptable as solutions in the movement towards decarbonization. Approval by the EU Commission and parliament seem likely. However, the waste and safety concerns mentioned above will still need to be addressed.

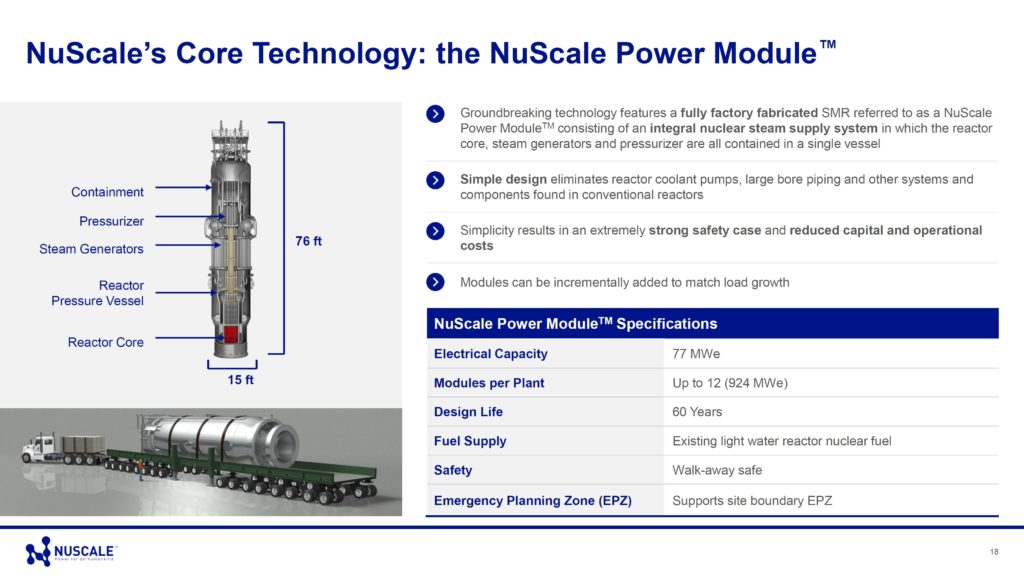

This points to the other very positive trend: the advent of SMRs (small modular reactors).

SMRs, being developed by companies such as Rolls Royce [UK: RR] in the UK, EDF [FR: EDF] and Areva SA [FR: AREVA] in France, and NuScale Power and Arc Clean Energy in the U.S., are self-contained nuclear plants that inherently solve some of the safety, cost, and construction problems associated with traditional utility-scale nuclear plants. Typically they generate about 300 MWe, compared to about 1600 MWe for a traditional plant, have an accelerated construction timeline, and have “walk away” safety, i.e. would shut down automatically and safely in the case of an accident. For this reason, some designs have already been certified by regulatory authorities not to need the large surrounding exclusion zone required by traditional facilities, so their footprint is much smaller. They are therefore suitable for a wider range of locations, including (for example) remote locations and inside decommissioned coal-fired plants.

Source: NuScale Energy

The first SMRs will begin to roll out in the late 2020s in the U.S., and in the 2030s in Europe. We believe this technology is going to be very significant for energy price and supply stability in Europe in coming decades. It is likely — as all things run in cycles — that the current enthusiasm for unrealistic and unworkable energy solutions in some European countries will encounter the dissatisfaction of the electorate as energy-driven inflation and the inconvenience and anxiety of supply disruptions continue. French and British firms are leaders in development of the technology. Even Germany may walk back its recent decisions, and may embrace SMRs as a solution moving forward that both sidelines Russia and allows a place to both climate and economic goals.

Investment implications: We are bullish on the future of SMRs, though the technology is new. There will be pure-play ways to approach this theme; investors should watch for private SMR-related companies coming public. Some large European industrials will also benefit, though obviously with less dramatic effects on their growth profile; we are thinking of leading European industrial/tech companies such as Siemens [GR: SIE]. And of course, in this context, we are long-term bullish on uranium and its supply chain participants.