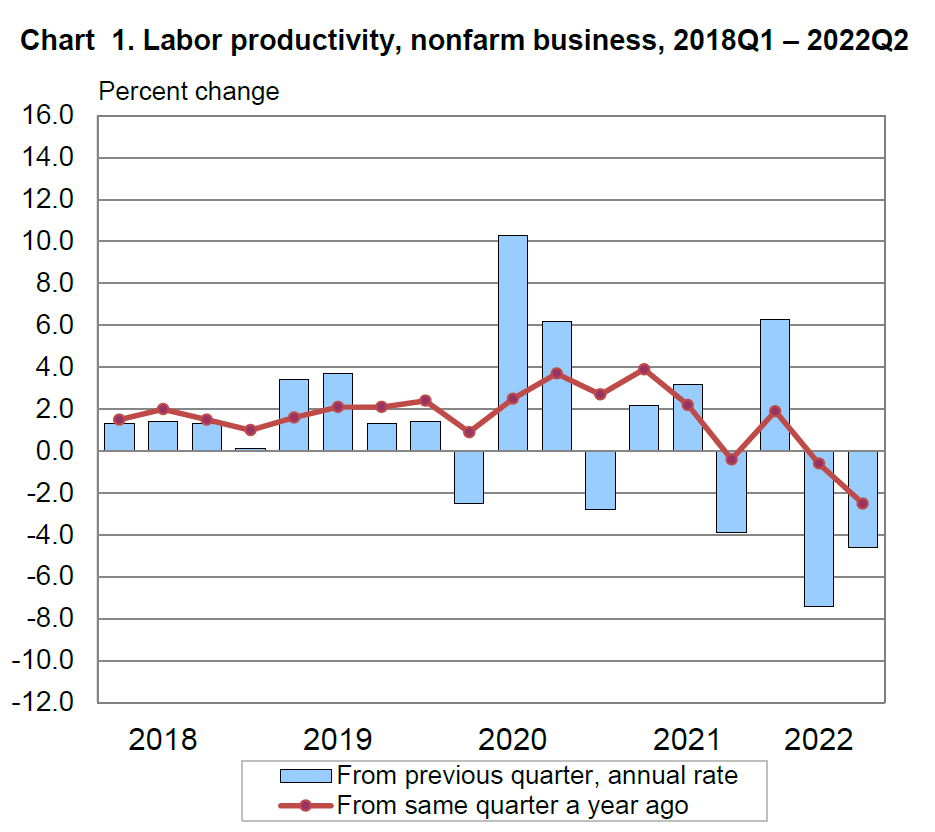

Last week the Bureau of Labor Statistics published its preliminary second-quarter report on labor productivity and labor costs. The headline numbers were worrisome — showing the second quarter in a row of sharp declines in non-farm labor productivity. The decline improved a little month-over-month, but year-over-year it was the sharpest seen in the history of the data — which go back to 1948.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Why Productivity Trends Are So Important

Of course, inflation continues to be front and center in investors’ and analysts’ minds. Inflation is closely related to productivity growth. Population growth alone can raise a country’s GDP — but only productivity growth increases GDP per capita, and therefore overall living standards. Productivity growth derives from capital expenditure on plant and equipment, and from all forms of technological innovation and improved production processes. Of course this applies to both goods and services across the whole economy.

In this virtuous cycle, capital expenditures and new technology and techniques increase workers’ economic output per unit of time, increase real wages, and decrease real prices (they make labor more valuable, and make the supply of goods and services more plentiful). The last thing an economist wants to see during an inflationary episode is collapsing productivity growth. When productivity growth declines, output per hour of labor across the economy falls; labor becomes less valuable in real terms, and the supply of goods and services per capita shrinks. Other things being equal, that would become another factor at work leading to inflation.

That’s pretty much what we’re seeing now: productivity is falling, real wages are falling, and the cost of living is rising.

What’s Going On?

The question is what is driving the productivity decline, and there are several plausible answers — and all of them probably have some truth. We must remember that productivity data are themselves generated from extremely high-level, abstract data sets — and that therefore there are many ways that those abstract data sets can be inadvertently or deliberately misconstrued. It is always worthwhile to look at the high-level data, ask yourself how it would look in the real world of company operations if your theories were true, and then listen to what company managements are saying to see if they confirm or cast doubt on your theories.

First theory: the decline is not real — it’s an artifact of the unprecedented pandemic “start and stop.” When the pandemic hit, and lockdowns and stay-at-home orders were imposed, tens of millions of workers became unemployed. Of course, the jobs lost were heavily and disporortionately in low value-added service occupations. Because these jobs tend to produce less economic value per hour of labor than higher-skilled jobs, their temporary removal from the economy caused the overall apparent productivity of the remaining workers to rise — which can be seen clearly in the BLS chart above. The first two quarters of the pandemic saw an extraordinary jump in productivity growth. But it was only apparent, and as lower-skilled workers have come back into the workforce, the year-over-year and quarter-over-quarter productivity growth numbers have plummeted. That too may be only an apparent decline — not of lasting significance.

Second theory: the decline is an artifact of unusual pandemic GDP dynamics. Since the overall non-farm productivity data are calculated basically by dividing GDP by hours worked, the violent swings in inventories and imports that have affected GDP this year would consequently also cause merely apparent swings in productivity growth. This could be another reason why some of the productivity downturn is just a statistical mirage.

Third theory: businesses put off capital expenditures during the pandemic, and productivity is suffering as a consequence. If this is true, it is in the process of beginning to right itself, as capital expenditures have been one of the bright spots of the GDP calculations in 2022.

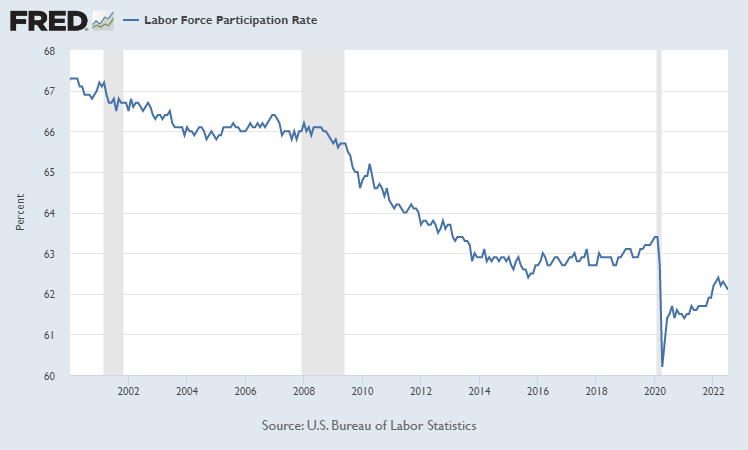

Fourth theory: the “Great Resignation” has changed the composition of the labor force, and preferentially removed higher-skilled, more value-adding workers. The pandemic hastened retirements among older workers (again, disproportionately higher-skilled) and led to burnout for many mid-level service workers — while simultaneously boosting all kinds of benefits to make it easier for workers to ratchet back their labor force participation. As we showed you last week in our discussion of why you have to look closely at the employment data, the labor force participation rate is still far below pre-pandemic levels.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

Similar to the initial stages of lockdowns, this would lower overall productivity — but unlike those short-term measures, this effect would be more than just a statistical blip.

Fifth theory: work-from-home is not good for productivity in all businesses — and may be quite lousy for many. The pandemic saw an unprecedented experiment in remote work. Some companies thrived; many others gradually determined that work-from-home among their teams was harming productivity. We heard the first negative reports from some tech startups, who said that remote interactions could not replicate the intense collaboration and idea generation of physical proximity. Some large financials were among the first to crack, instructing workers to get back to offices in New York. (The CEO of Morgan Stanley pungently commented that “If you can go out to a restaurant in New York City, you can come into the office.”)

Now big tech companies — some of them, the very innovators who helped make work-from-home possible — are trying to get their employees back to the office. Apple [AAPL] wants corporate workers on site for at least three days a week by Labor Day. Bank of America reported of Alphabet [GOOG] that “a few days ago, Sundar Pichai (CEO) reportedly told employees to improve productivity and also asked them for ideas on how to get ‘better results faster.’ ‘There are real concerns that our productivity as a whole is not where it needs to be for the headcount we have,’ he said. Also, employees who work in the Google Cloud sales department have reportedly said that senior leadership told them that there will be an ‘overall examination of sales productivity and productivity in general.’ This comes after the company announced a two-week hiring freeze in July, which may be ongoing.” Over at Meta Platforms [META], Mark Zuckerberg said that he wants “to get more done with fewer resources.” The tight labor market is still giving workers the ability to push for work-from-home if they want it (not all do), but the writing is on the wall that normality is returning even to the world of tech.

If work from home were the universal panacea advertised at the beginning of the pandemic, you can be sure that these pragmatic tech firms would still be embracing it — but they aren’t. If they see productivity falling from work-at-home, it’s a safe bet that this decline is a reality in many other sectors too.

Investment Implications: Each of the explanations offered above for this year’s sharp productivity decline probably has a grain of truth. Some of these suggest that the trend will quickly normalize; others suggest the productivity drag will be more lasting. We know the importance of productivity growth for the economy as a whole, but more to the point, business owners and managers know the importance of productivity growth for their own operations, their profits, and the wellbeing of their employees and other stakeholders. That makes us all the more perennially bullish on companies that are enablers of productivity growth — primarily in the technology sector, but also in tech-adjacent corners of other sectors, particularly finance, defense, and healthcare. Even if the overall economy is experiencing a productivity swoon, there will still always be individual companies who will prosper when they deliver productivity-enhancing innovation to their customers — so let that be a permanent and prominent part of your investment idea generation. We are happy to see the pragmatism of companies such as AAPL, META, and GOOG when it comes to evaluating the real productivity success and failure of work-from-home policies. It may work for some, but as it turns out, it does not work for all — or works only within limits.