The total value of residential real estate in the U.S. is about $34 trillion — about the same as the total market capitalization of all publicly traded U.S. companies. But while technology has made the stock market much more efficient — allowing transactions to happen with greater ease and speed, and ever lower costs — real estate transactions by comparison remain slow, complex, and expensive.

Certainly, real estate is different from stocks. Two shares of Alphabet [NASDAQ: GOOG] are identical and interchangeable (“fungible,” in financial language), but two pieces of real estate can differ in hundreds of meaningful particulars, even when they are geographically and functionally similar.

However, not all the factors of real estate that make transactions difficult and expensive are intrinsic to real estate as an asset class. Some of these inefficiencies come from oligopolistic practices within the real estate industry — where incumbent industry participants and organizations have cemented historical advantages that really derived from old technology and information asymmetry. These historical advantages have let incumbents sit between buyers and sellers and receive handsome compensation for the service of putting the two together — much as brokers once did in the stock market.

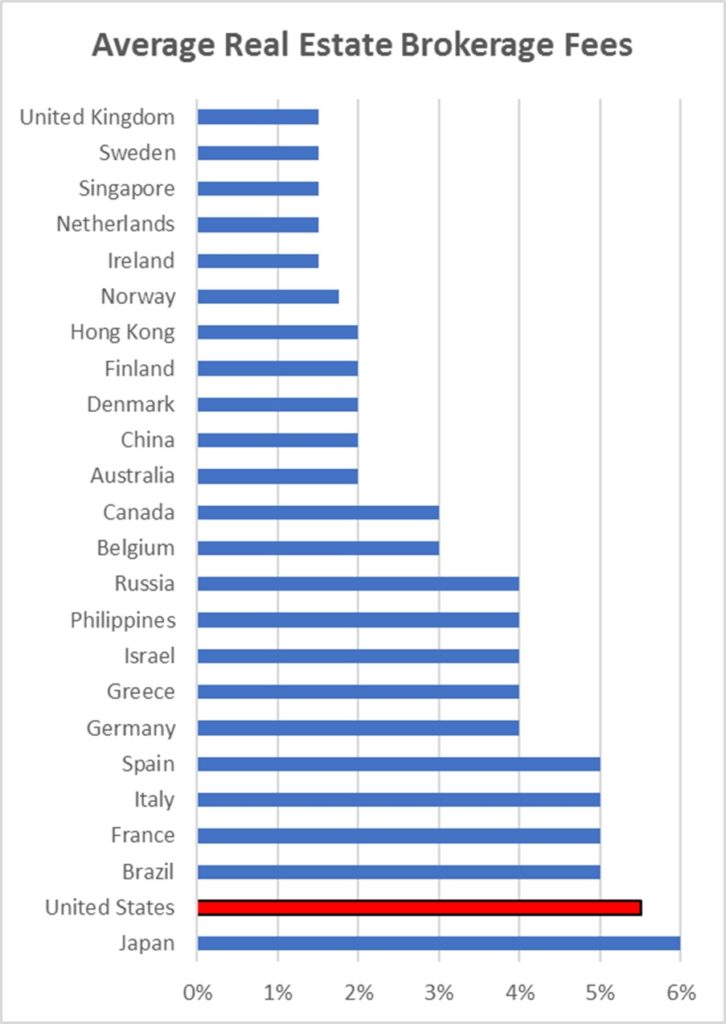

Of course, to paraphrase Amazon’s [NASDAQ: AMZN] Jeff Bezos, “Your handsome compensation is my opportunity.” In other markets — for goods, for services, and for securities — digital platforms and hardware and software innovations have relentlessly squeezed the middlemen’s cuts. That process is just beginning to occur in residential real estate. In the United States, brokers’ fees on a residential real estate transaction average about 5–6%, in 2019 totaling about $75 billion on $1.5 trillion in transactions. In contrast, $40 trillion worth of stocks changed hands, with fees to brokers at just $10 billion. This obviously presents a rich opportunity for disruptors.

Inefficiencies and frictions in real estate transactions have implications beyond the immediately obvious. For one thing, much of the U.S.’ historic economic dynamism has derived from the willingness of workers and aspiring entrepreneurs to relocate in search of new opportunities. Costs and frictions in real estate transactions inhibit that process, and so have a definite, if hard-to-quantify effect on economic growth.

The U.S. is virtually alone among developed countries in having such high residential real estate transaction costs; only Japan is higher. Surprisingly, the U.S. ranks above European countries with stringent and not always consumer-friendly regulatory regimes.

The U.S. seems to be an outlier primarily because of a lack of competition. Unlike in many countries, the seller usually pays fees to both their own agent and the buyer’s agent; so studies have found that properties with low fees are less likely to sell than those with higher fees (the reverse of what one would expect to find under free-market conditions). The primary database for home listings — the Multiple Listings Service, or MLS — has been the subject of anti-trust investigation and legislation, to see that its data are not misused or tacitly restricted to inhibit access by low-fee sellers and agencies.

Granted that some residential markets are “bespoke” by nature, many are more uniform. In those, there is more scope for the application of big data and artificial intelligence to reduce fees. Some new companies entering the “prop tech” market use their data and software to value houses, make “instant offers” to sellers, and buy their homes as inventory to sell on in similar low-fee transactions to the eventual buyers. In this, they are, in a way, emulating situations in which market-makers hold inventory (such as bond markets) before selling on to the eventual buyers. They are also replacing much of the valuation and local know-how of agents with big data. Our bet is that they will be increasingly successful, and that eventually, agents will find their bread and butter primarily in the high-end markets that resist such standardization.

These “prop tech” companies — such as Compass [privately held], Opendoor [privately held], Redfin [NASDAQ: RDFN], and Zillow [NASDAQ: ZG] — are approaching the tech disintermediation of traditional agents and brokerages in a variety of ways: some acting as instant buyers, some offering online listings, some offering suites of tools to agents to make them more productive.

With new Justice Department investigations of industry anti-competitive practices underway (the first in ten years), as well as two large class-action lawsuits in process, we think it is likely that the industry will continue to come under pressure, creating an ongoing opening for the “creative destruction” of the tech interlopers. Watch this space.

Investment implications: Residential real estate is one bastion of resistance to the storm of disintermediation unleashed by the internet, software, and artificial intelligence. But the high fees paid in the U.S. for residential real estate transactions present an irresistible opportunity for “prop tech” companies to rationalize, streamline, automate, and squeeze out the excess. The near-term prospects of some of these companies are unclear, as they attempt to scale into challenging new businesses such as “instant buying” from sellers, but they should be a long-term focus of interest for investors.

Please note that principals of Guild Investment Management, Inc. (“Guild”) and/or Guild’s clients may at any time own any of the stocks mentioned in this article, and may sell them at any time. Currently, Guild’s clients own AMZN and GOOG. In addition, for investment advisory clients of Guild, please check with Guild prior to taking positions in any of the companies mentioned in this article, since Guild may not believe that particular stock is right for the client, either because Guild has already taken a position in that stock for the client or for other reasons.