As expected, the Fed hiked rates by 75 basis points on Wednesday, with a 50 or 75-basis point hike on deck as well for July. Whatever the very temporary immediate response of the market, it focuses attention very clearly on the inflation and interest rate trajectory. For the majority of investors and advisors, who rely on bonds in their portfolios, it should occasion some intense soul searching.

What’s Ahead For Bonds

In March and April, we wrote a little about bonds, and about the likely future fate of traditional, indexed, 60% equity/40% bond investment portfolios in the context of the Fed’s liftoff from zero interest rates.

“Those who can avoid bonds in their investment allocation should do so. The decline experienced thus far by bondholders does not yet give a clear picture of how bad we believe it could get. One analyst we read recently noted that many credit strategists are preferring to take default risk over duration risk. In layman’s language, that means that they would rather own short-term junk than long-term quality — because they’ll be out of the short-term junk quickly, but the long-term bonds, even if they are high quality, will be crushed by rising rates…

“The shelf-life of the traditional, indexed, 60/40 portfolio is close to expiration [we would now say it’s there]. Bonds were long thought to be — and long functioned as — counterweights to the equities in a portfolio, and would blunt volatility, since they were negatively correlated. They are now positively correlated, as both stock and bond indexes are at historically abnormal valuations, and heading into an era in which inflation and rising rates will challenge the valuations of most long-duration assets… Needless to say, we would avoid bonds. Bond yields are now not paying enough for the risk you’re taking when you go beyond cash-equivalent very short-term paper.”

What It Means For Your Portfolio

There are two points here that bear repeating. And those two points factor into a wider reality that we’ll sketch after we describe them.

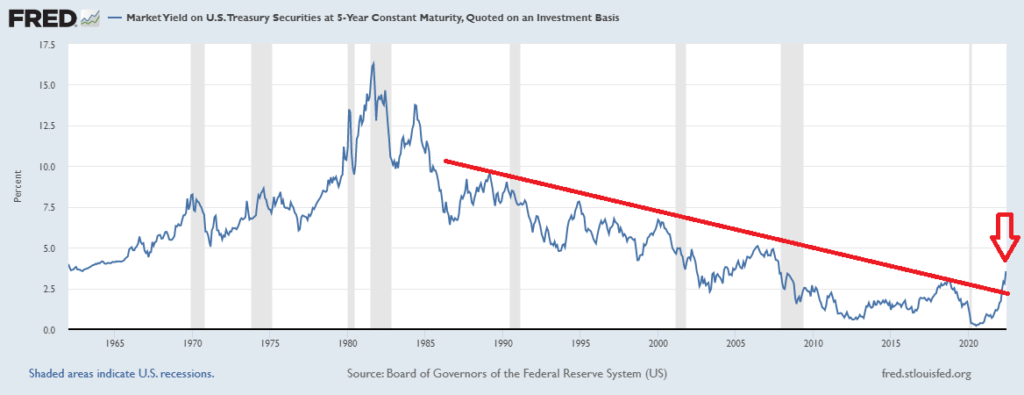

First point: the assumptions underlying the portfolio construction and the financial products that have become the bread and butter of the retirement industry will be challenged by the end of a decades-long trend of falling interest rates. You can see the breakout here, illustrated in the long-term chart of five-year U.S. Treasury interest rates:

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

Since the market value of a bond rises as interest rates fall, this multi-generation secular trend of declining interest rates has served as a constant tailwind to portfolios with a programmed bond component. In recent years, the 60/40 model has developed further into the “target date fund” — a fund with equity and bond index components that adjust automatically to give more weight to bonds as the retirement date approaches. A large portion of institutionally managed retirement accounts for U.S. workers are funneled into funds like these. Unless your investments are managed by Guild Investment Management, or a manager who thinks like we do and who is not constrained by some blend mandate, then it probably contains a sizable allocation to bonds — and there is probably no plan in place to change that position.

For decades, investors have been told that bond allocations will reduce volatility and boost “risk adjusted returns” — and they did so, from the mid 80s until this year. This year, however, bonds and stocks have become positively correlated, removing bonds’ utility as “volatility dampers.” And looking further out, the new environment of persistently higher inflation will mean persistently higher rates — an end to the performance tailwind bonds once provided. Bonds will no longer help; they will begin to hurt, just as they have thus far in 2022.

Second point: The sea-change in inflation and therefore in interest rates will affect not just bonds, but stocks as well. The price of a stock is determined by how much investors are willing to pay for a stream of future earnings (which will either be returned to them via dividends or buybacks, or rolled back into the company to allow it to grow). How much they will pay depends, other things being equal, on the “cost of money” — that is, on prevailing interest rates. Other things being equal, as interest rates rise, people will be willing to pay less for a stream of future earnings; in other words, the price-to-earnings ratio will fall. And if earnings themselves are also falling — as they do during a recession — the price of the stock itself will also fall.

Thus, on a market-wide level, the majority of investors and savers, who have for decades been plowing more and more into passively managed broad index funds of both bonds and stocks, are facing a situation in which everything is going down at once. And more significantly, the long-term change of trend in interest rates suggests that this is not going to be a brief episode followed by a restoration of the old status quo.

The decades-long regime of constantly falling interest rates, in short, led to distortions in investment strategy. We could call them “cheap money” strategies, in which the rising tide of cheaper and cheaper money “floated all boats”… keeping interest rates down and boosting bonds, and pumping indexes to highs that were unmoored from fundamental reality. This trend reached a crescendo during the pandemic stimuli and their aftermath, but it is now breaking down. The declines have further to go. Even if the overall market’s price-to-earnings ratio would be historically “normal” at 17 or 18, the experience of the 1970s suggests that unhinged inflation, recession, constrained energy supplies, and geopolitical turmoil could see the S&P 500 trade at a price-to-earnings ratio of 14 or 15. It is a historically accurate rule of thumb that investment trends that reach exponential excesses don’t correct neatly to their long-term average… they overshoot on the downside. So we suggest that S&P 500 is still too expensive if earnings are on the decline. However, within the S&P 500, there will be companies and industries who have rising earnings, and will far outperform the market. Look at these areas for opportunities.

Can’t the Fed Just Start the Printer Again?

Why can’t the process just start all over again? When the debt supercycle began in the 1980s, U.S. Federal debt to GDP stood at about 30%; by the ending of this supercycle, which we believe we are now witnessing, it is at nearly 140%. That’s well above the level at which the consensus of economists suggests that negative effects begin to accrue to GDP growth. The short and sharp truth is that the supercycle is ending because it has reached an extreme, and to continue the easy money policies through yet more programs of easing would risk economic ruin. The Fed is not going to ride to the rescue this time, at least, not at the scale at which it has in the recent past.

Other Effects: The Capital Destroyers and Dream Factories

Long periods of cheap and ever-cheaper money lead inexorably to a lack of discipline in spending it. Market-wide, this results in excessive price-to-earnings ratios. In the post-2008 period when quantitative easing came online to add a new dimension to “easy money,” this allowed venture capital to finance a new generation of businesses whose entire focus was on customer acquisition rather than on profitability.

Many of the leading companies of the “gig economy” are examples. Young urban consumers got used to a lot of “on demand” services — such as transportation and food delivery — that were ultimately priced below what would be actually profitable, and were ultimately subsidized by venture capital (hence our moniker of “capital destroyers”). When money is priced too cheap for too long, these distortions happen… but investors are now seeing that no trend lasts forever, and those companies whose business models can’t adapt to higher rates and tighter financial conditions will not survive in their present form.

Of course, other manifestations of the speculative madness enabled by “cheap money” include hedge funds (more and more of which are now going belly up) and the over-proliferation of cryptos, where there have been some spectacular crashes recently. Despite the new shine that accrues to crypto from its innovative technology, the collapse of projects like Celsius is always traceable in the end to the same thing that has brought speculators low since the beginning of time: over-leverage in optimistic times that unwinds itself catastrophically when the good times end.

(Please note: we still believe that bitcoin is a phenomenon that will persist, and have a long-term role as a scarce digital asset and wealth preservation tool. But it is likely that further declines lie ahead, brought on both by the general tightening of financial conditions, the draining of speculative fervor, and the unwinding of large and unknown levered entities in the crypto space.)

What Is the Solution?

We believe that so many phenomena of recent decades, which reached their high-water mark during the pandemic stimuli, are related to the “free money” distortion that is now being corrected by the reality of inflation and the reality of higher rates. Portfolios reliant on index funds and on bonds are a key example. We believe that just as there are significant echoes of the 1970s in present economic and geopolitical conditions, there will be significant lessons to learn from investors of that era in shifting investment strategy to new patterns that will work in the present environment.

What are those new patterns?

First and foremost, a return to fundamental analysis and active management. A generation grew accustomed to “auto-pilot” returns from indexes, and in an era of scarcer capital and more constrained financial conditions, the indexes are likely to be challenged. Interest will rise in the old-fashioned analysis of the finances, operations, and prospects of individual companies, and we believe, more investors and managers will return to the construction of portfolios of individual securities. (There may even once again be a value in the fundamental analysis of small companies, which have reached their largest-ever divergence in valuation from large.) The sooner investors make this shift, the more likely they will be to avoid what we have called a “lost decade” — a prolonged period of malaise for the broad market indexes.

Second, a return to pragmatism. Infinite amounts of extremely cheap money distort priorities and allow for the flourishing of economic and social conceits. We believe that the true costs of extremist agendas of all kinds, when seen against the backdrop of more scarcity and a challenged standard of living, will bring some legacy industries, such as hydrocarbon energy, out of the cold. Uninvestable pariahs may again begin to be seen as necessary supports of growth and prosperity — industries to be managed and regulated, but not eliminated.

Third, a return to commodities. Scarcity won’t just mark hydrocarbons and energy; other scarce resources and commodities, we believe, will also return to their place in investors’ portfolios. Of course, gold and other precious metals are among the most important. While a rising-interest rate environment is challenging for gold, as is a strong dollar, gold’s long-term historical role as a portfolio diversifier and volatility damper may once again rise to investors’ minds — especially if the bonds they have come to rely on for those purposes enter a prolonged period of poor performance.