U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross recently took a trip to Australia to help strengthen commercial ties between the two close allies. One of the key points of his visit was to lay the groundwork for discussions of a “U.S.-Australia Critical Minerals Action Plan” that will be finalized in November. Australia has the world’s second-largest reserves and second-largest production capacity of rare earth minerals, and Ross is following through on U.S. plans to encourage the development of rare earths supplies outside of China. The Australian government has expressed its desire for greater investment by U.S. firms, and hopes that rare earths projects will be a good pipeline for such projects.

We wrote about rare earths, and about the problematic dominance of China in the production of these minerals, back in May. Here is our backgrounder on their significance in the context of current technological trends and geopolitical developments.

Some Background on Rare Earth Minerals and Their Importance

We’ve often written that the balance of power in the conflict between the U.S. and China is unequal — China is far more vulnerable to U.S. actions and sanctions than the U.S. is to China’s. One weak spot that has often appeared in media coverage is “rare earths” — a topic we have addressed in previous years in these pages.

“Rare earths” are elements, primarily in the lanthanide series of the periodic table of the elements, that are small but critical components of many modern technological products — especially batteries, magnets, lasers, exotic alloys, catalysts, nuclear controls, and advanced glass formulas for screens and lenses. They are not particularly “rare” — the most plentiful of them exist in the earth’s crust in greater amounts than minerals such as copper — but were named at the end of the 19th century because they existed in complex mineral deposits and were then challenging to mine and refine.

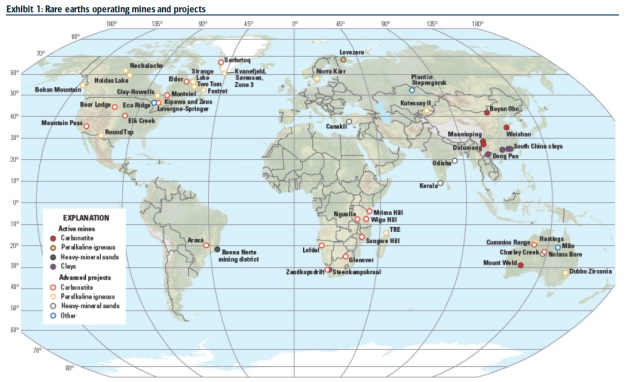

Rare earths deposits exist plentifully in many places around the world.

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch Research

However, although deposits are so widespread, production is currently not. Until the 1980s, the U.S. was the main producer, but over the course of the 1980s and 1990s, the Chinese government decided intelligently on the strategic value of rare earths. With government support, Chinese producers undercut their competitors, and production elsewhere in the world gradually shut down. The largest U.S. mine remains shuttered.

The U.S. Department of Defense report that came out last September on the security of the U.S. industrial supply chain noted the importance of rare earths in particular:

“As part of the increasingly global manufacturing and defense industrial base, imports of strategic and critical materials, such as rare earths, have increased, causing a trade-off between supply dependency and lower costs. Rare earths are critical elements used across many of the major weapons systems the U.S. relies on for national security, including lasers, radar, sonar, night vision systems, missile guidance, jet engines, and even alloys for armored vehicles… China’s domination of the rare earth element market illustrates the potentially dangerous interaction between Chinese economic aggression, guided by its strategic industrial policies and vulnerabilities and gaps in America’s manufacturing and defense industrial base. China has strategically flooded the global market with rare earths at subsidized prices, driven out competitors, and deterred new market entrants. When China needs to flex its soft power muscles by embargoing rare earths, it does not hesitate, as Japan learned in a 2010 maritime dispute.”

That muscle flexing was recently demonstrated when Chinese President Xi Jinping visited rare earths production facilities in China’s west — a visit clearly intended to underline China’s dominance in this area.

The critical thing for investors to appreciate is that even here, China’s threat lacks real bite. Supply chain disruption would occur in the short term if the U.S. had to source technological products from non-Chinese manufacturers; even a ban on rare earths exports to the United States would be incomplete because of such trans-shipments. It would be a headache for the U.S., not a catastrophe. In the long term, there are abundant rare earths deposits outside China; they simply need to be developed (or re-opened, in the case of the U.S.). As such ex-Chinese production ramps up, known reserves will also expand — we note that Brazil’s deposits are already known to be rich. The U.S. would be wise to use the current realignment of priorities to encourage rare earths production outside China — especially given the increasing role that will be played by advanced batteries in global transport over the coming decades.

Investment implications: Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross’ visit to Australia shows that the U.S. administration is making progress in encouraging the development of rare earths sources beyond China. The progress towards a “U.S.-Australia Critical Minerals Action Plan” should further allay any concerns that investors have that China could use its dominance as a weapon against the U.S.