We say it often and we will say it again: earnings are the mother’s milk of stock prices. On a market-wide basis, a flat or declining earnings trend almost invariably accompanies a flat or declining trend in stock prices. This doesn’t mean that investors should go completely to cash (particularly when inflation is running hot); but it does mean that they should make greater efforts to identify the industries that can prosper under prevailing conditions, as well as other asset classes, e.g. commodities, that will appreciate. Needless to say this is not a trivial task.

Analyst consensus estimates now put the net income of S&P 500 companies as a whole at 4.3% year-on-year growth during the first quarter (earnings per share is up 6.4%, but the net income number strips out the effect of share repurchases). But with inflation running at a 7.9% pace, that means that in real terms, earnings growth is now negative. Strip out the effect of the spike in the energy sector’s revenues (which at present represents only about 3% of the S&P by market capitalization), and the rest of the S&P 500 is probably tracking about a 7% earnings decline compared to last year. If this situation persists for another quarter, we can fairly call it an earnings recession.

“Will it persist?” is therefore the question, so let’s seek to answer it.

What’s Really Driving Markets Now

The immediate impacts of the Russian war in Ukraine have continued to dominate headlines, with revelations of atrocities that if true rival those committed by the Red Army during the Second World War. Underneath those headlines, however, what is most significant for an analysis of markets are the actions and intentions of the Federal Reserve.

In 1973, war and the political turmoil surrounding it were the spark for an energy-focused inflationary crisis. Today, the war in Ukraine is intensifying and prolonging the powerful inflationary impulse that really originated in the pandemic-related easing measures undertaken by the Fed and the Treasury. That impulse has likely broken the “lowflationary” environment that had prevailed since Fed Chair Volcker slew the inflation dragon in the early 1980s — marking an epochal shift. The arrival of this current inflation, which we believe will decline only slowly and will last for many years, is calling forth a Fed policy shift for the ages. That shift will have profound effects, and is the most important factor currently at work in markets, even when headlines are directed elsewhere.

One thing that makes today quite different from the last big inflationary period is that debt levels — both government, corporate, and private — are much higher today than they were then. In 1979, US non-financial-sector debt was 140% of GDP, and government debt was 40% of GDP. Since then, those have risen to 283% and 124% respectively. Since the economy as a whole has become more levered, the effect of tightening will be more rapid, especially if the Fed is simultaneously raising rates and reducing its balance sheet.

That is precisely what it intends to do. While the minutes of the last FOMC meeting, released on Wednesday, stop short of indicating the start of the balance-sheet runoff, they suggest clearly that it will be soon — likely after the May meeting. The minutes show that the runoff will be more aggressive than consensus believed — probably $60 billion in Treasuries and $35 billion in mortgage-backed securities each month — and will be coupled with rate rises, likely including several 50-basis-point moves.

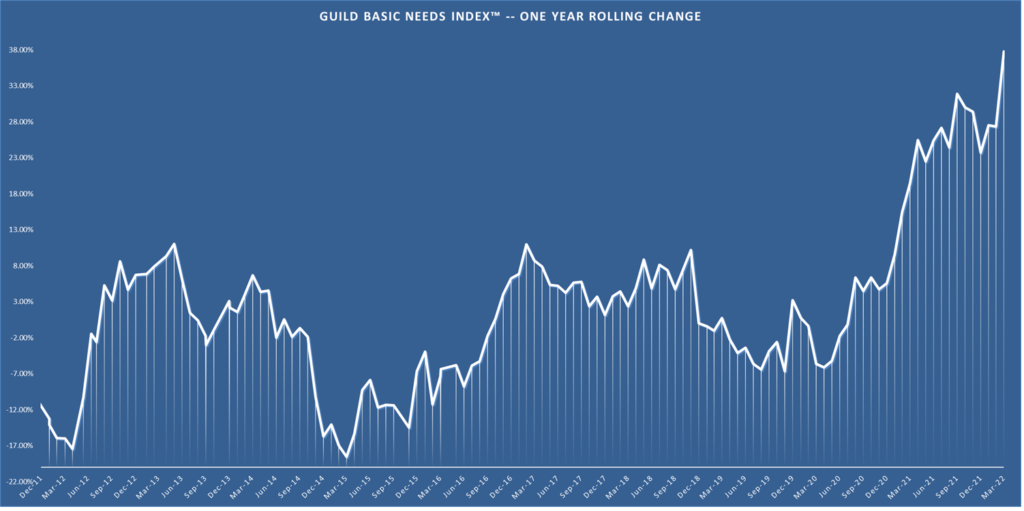

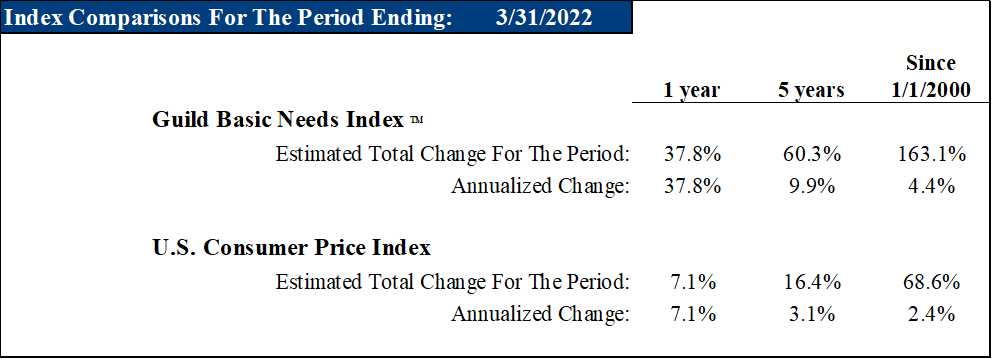

The minutes noted that intense inflation in living expenses — the kind we track with our in-house real-world inflation gauge, the Guild Basic Needs Index — presented a significant risk of embedding inflation expectations. To translate, that means that when consumers experience such inflation, it becomes like economic kudzu vine — rampant and extraordinarily difficult to eradicate. The minutes note:

“A few participants judged that, at the current juncture, a significant risk facing the Committee was that elevated inflation and inflation expectations could become entrenched if the public began to question the Committee’s resolve.”

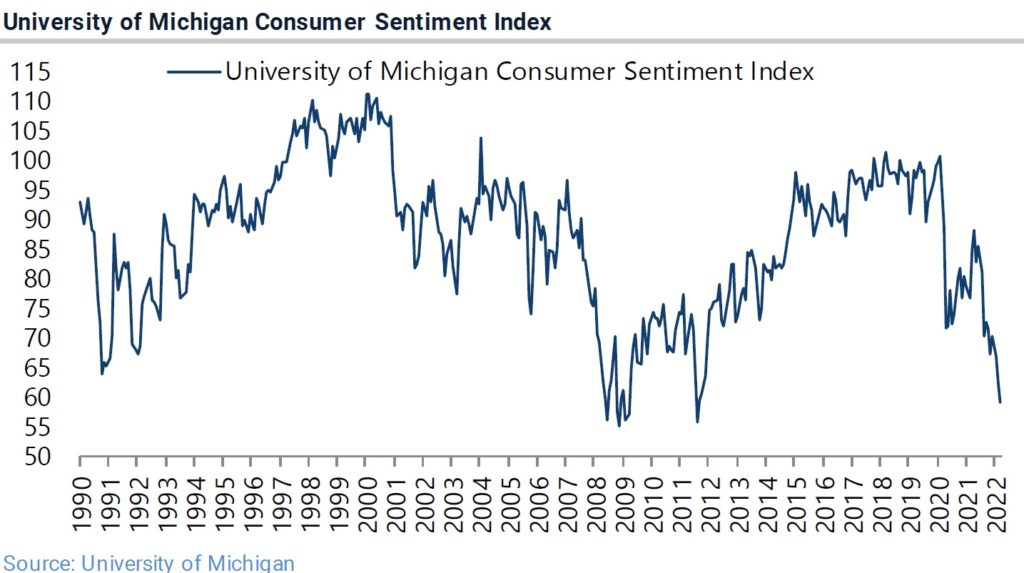

Perhaps the Fed was looking at the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index, which has fallen off a cliff to levels not seen even during the pandemic lows:

Source: Jefferies

While we do not yet have all the March data for the GBNI, the preliminary result is sobering: our measure of consumer basic needs is rising at a 37.8% year-on-year rate — and that’s before including the data points that pertain to some food and housing components.

Will There Be A “Fed Put” This Time — And If So, When?

At this juncture, the Fed is feeling a particularly intense need to control inflation — perhaps overriding many other considerations. The Committee understands that its credibility is on the line — and is therefore more likely to push the tightening envelope, even if it results in economic or market displacements.

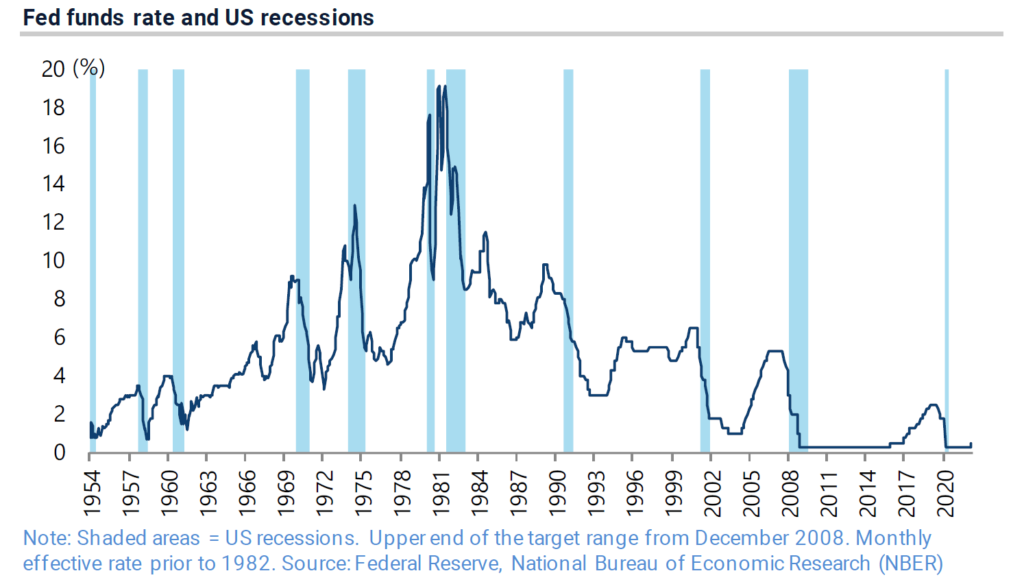

Clearly, a recession is in the cards — exactly when, we do not know; but every major tightening episode of the past 70 years has been followed by one, and this is a major tightening episode by any measure.

Source: Jefferies Research

The leadup to this recession will likely be characterized by “stagflation” — persistently high inflation and anemic economic growth. However, so far, the consensus of analysts is lagging the emerging reality. 2022 GDP growth consensus was 3.9% at the end of last year — and has thus far only been cut to 3.5%. This does not gel with what we see in first-quarter earnings — implying a disconnect between the top-down macro analysts and the bottom-up company-level analysts. Once again, it will be extremely important to listen to company managements discuss their rest-of-year outlook on upcoming conference calls — possibly to offer a corrective to too-rosy macro views of the economic trajectory.

At some point, the Fed is likely to find itself tightening into the teeth of significant market turmoil — and the question is when the “Fed put” comes into play. We do believe the Fed put — the point at which the Fed acts to support markets — is still in play; the Fed is more politicized now than it has been for many decades (or perhaps we just have a clearer view of how the sausage is made). However, we believe that the confluence of current conditions makes it likely that the Fed will be willing to see more volatility than people think before easing off its tightening plans.

Thinking Longer Term

Above, we noted the “epochal” nature of the Fed’s shift. We would be remiss not to note that there are many factors at work here which suggest a sea-change in the inflation landscape — and therefore in the investing landscape. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the sanctions imposed by the United States and the rest of the developed world, and the newly strengthening alignment of the world’s illiberal regimes (particularly Russia and China) very likely indicate a decisive shift in the nature of globalization. Increasingly, supply chains, financial interactions, economic relationships, and military alliances will be fractured into new, more defensive, more competitive, and more intensely inward-looking blocs. The consequences, we believe, will be broadly inflationary, because such de-globalization implies a host of new logistical, political, and military costs to be borne in the short to intermediate term.

Further, nearly universal demographic changes worldwide portend a shift from an epoch of plentiful and cheap labor to less plentiful and more expensive labor, as population growth continues to slow and as aging cohorts of workers drop out of the workforce. This implies both a long-term inflationary impulse driven by labor costs, and the possibility of significant political realignments.

Our Next Zoom Call

We’ll be hosting a Zoom call on May 5, following the Fed’s next meeting. We look forward to discussing all these topics in greater depth, and hope to see you there.