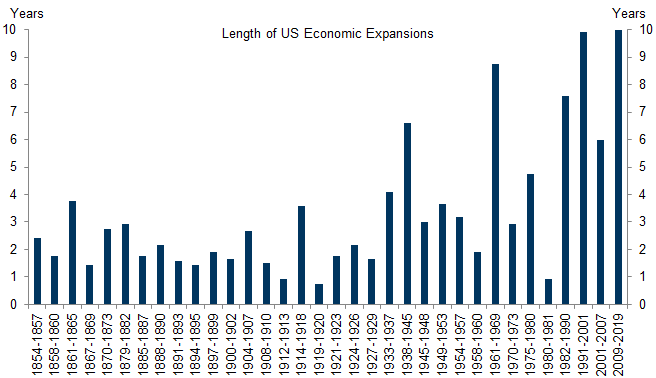

The Longest Expansion

The economic expansion that began in 2009 has now crossed the threshold and become the longest period of economic growth in U.S. history:

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

Of course, this milestone has led to two responses: analysts and central bank economists reminding us that “expansions don’t die of old age,” and critics responding first, that they do die of age-related diseases; and second, that there are some new global trends at work that might make this time different.

Both sides are right. There is no intrinsic reason why periods of economic expansion must end. Australia, although a very different economy from the United States in both composition and scale, has not experienced a recession since 1991. Still, as expansions age, risk factors do rise. The question then is whether we see those risk factors rising for the U.S. right now.

The first expansion killer is wage-push inflation. As expansions continue, the unemployment rate can fall to levels where wage gains heat up, create inflation, and lead central bankers to jump in and raise rates to keep inflation tame, thus ultimately causing credit to contract and tipping the economy into recession.

For a variety of reasons, this is not now occurring. Technology may be one of the main factors, helping keep inflation much more tame over the past 20 years than in previous economic cycles. In economist-speak, the “Phillips curve” has flattened — a macroeconomic measure of the relationship between unemployment and inflation. Tame wage growth and inflation, even in the face of a tight employment market, may lead to an environment where central bankers don’t need to intervene.

The second age-related illness that can afflict mature economic expansions is financial imbalance and credit stress. We discussed this above in our description of the big picture of China’s financial system. Boom times tend to generate financial excess, as low rates, psychological exuberance, and increasingly lax lending standards lead to the over-enthusiastic creation of debt.

Again, although there are distant signs of excess in some areas of the U.S. financial system — for example, in the leveraged loans increasingly favored by yield-starved pension plans — U.S. consumers remain in much more robust financial shape than in the late stages of previous expansions. Further, our favorite composite indicator, an index of more than a hundred financial stress indicators compiled by the Chicago Fed, shows so signs of stress in U.S. credit as a whole.

Finally, there are new things going on in the global environment (though we really believe the old saying that history doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes — and current events are usually not as unprecedented as they seem). The current global reassessment of the last few decades of globalization — AKA “the trade war” — is one of these. Here again, though, we continue to believe that the fallout will simply not be as catastrophic as some alarmed analysts believe. So far, the evidence suggests that trade conflicts are having a very limited effect on the U.S. economy — both in terms of consumer spending, and in terms of corporate expansion plans (that is, capex spending). If tariffs ultimately act as a tax on consumers in the nations that impose them, you could frame the current and likely future effects of tariffs as a small tax increase following a much bigger tax cut. In short, not likely to be an expansion killer.

Investment implications: The usual age-related diseases that crop up at the end of long economic expansions are not yet creating trouble for the economy of the United States. Conditions can change rapidly, of course, so we monitor a group of variables closely, including U.S. dollar strength, corporate profits, consumer and small business confidence, and overall credit conditions. For now, in spite of ongoing turmoil surrounding trade, the light is still green.