For several weeks we’ve been presenting data that offer reasons for optimism in the face of the covid pandemic. We see reasons to think that the public health dimension of the pandemic may be closer to a resolution than the consensus believes. Better understanding of the demographics of the most vulnerable covid patients; better “best practices” in treatment; a growing global pipeline of therapeutics; signs of viral mutation towards more benign strains; and emerging evidence of widespread T-cell cross immunity from the common cold all suggest that the pandemic’s impact may be contained well before the arrival of a safe and effective vaccine (if that ever occurs).

However, the public health dimension of the pandemic is not the only dimension that is relevant to investors. By far the largest social and economic ramifications of the pandemic are arising from the policy response by political, financial, and monetary authorities. To keep the public health dimension in perspective, consider the influenza pandemic of 1957/58.

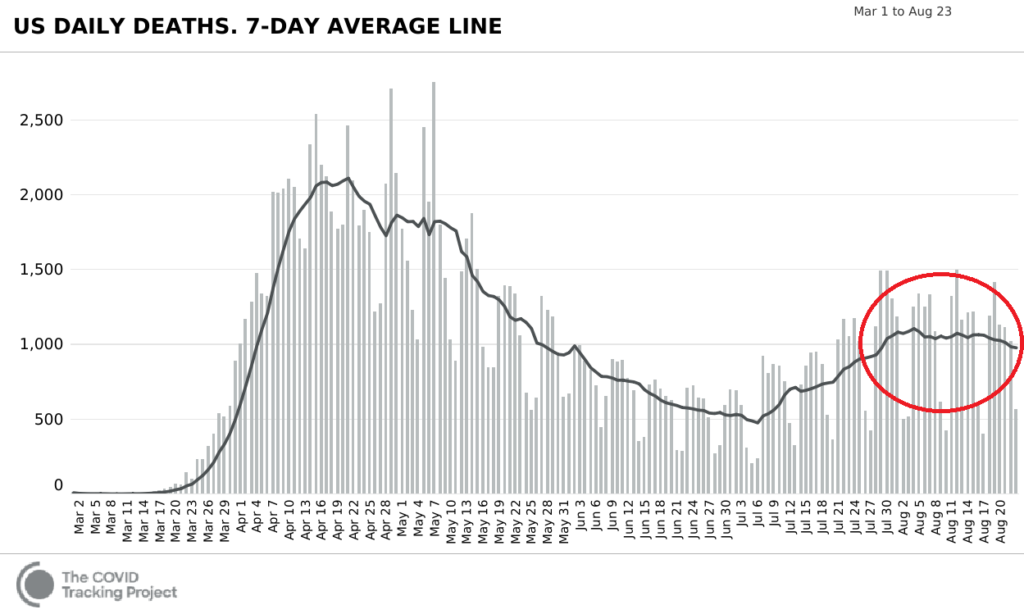

That pandemic killed 116,000 Americans in a country with half the current population of the United States. Covid-19 would reach comparable mortality if it crossed the threshold of 232,000 deaths; the current official total is 177,000. The rate at which that total is climbing is now trending down:

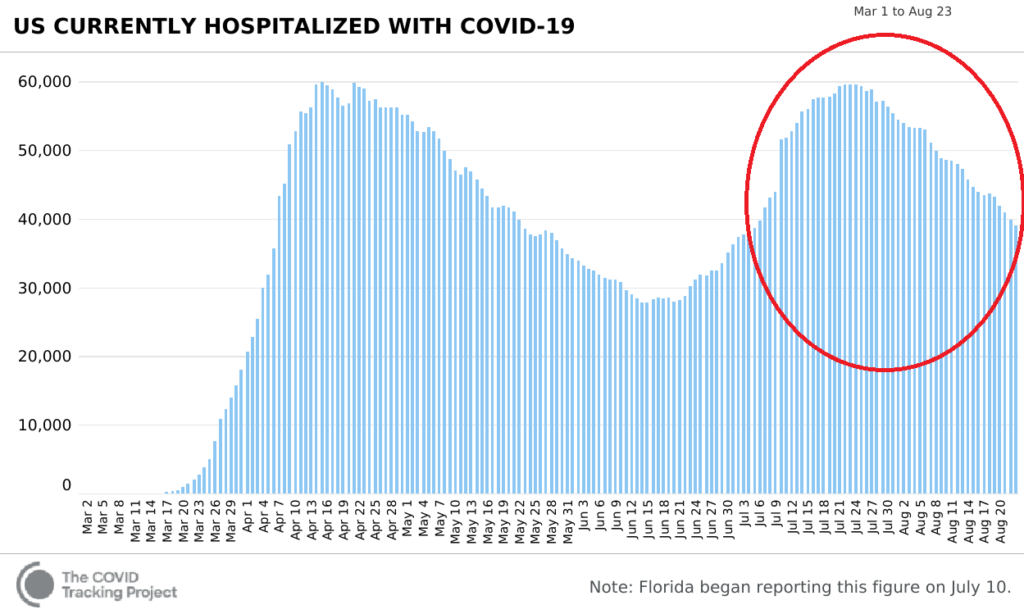

And hospitalizations are also declining, even though headlines continue to focus on increasing cases, which are predominantly among the far less vulnerable younger population:

In short, given moderating mortalities, falling hospitalizations, accelerating treatment improvements, refinement of measures to protect the vulnerable, and the possible arrival of “herd immunity” when SARS-CoV-2 infections reach ~20% of the population, the 2020 covid pandemic seems to be of about the same severity as the historically unmemorable 1957/58 flu pandemic.

If you ask most people under 70 about that pandemic, you will likely receive blank stares. From the perspective of history, that pandemic was far from the most significant social, cultural, or economic event of the time (the creation of the European Economic Community and the launch of Sputnik probably rank higher), and certainly did not prompt a massive and economically disruptive response from public authorities, or draconian social control measures.

For Investors and Retirees: Secondary and Tertiary Effects

Therefore, the most significant effects for investors are probably the “second order” effects of policy makers’ responses, and the “third order” effects of responses to those responses. These second- and third-order effects may already have taken on a life of their own.

Some of the most significant of these tertiary effects for investors and retirees are likely to concern demographic shifts accelerated by pandemic fears and pandemic policy responses.

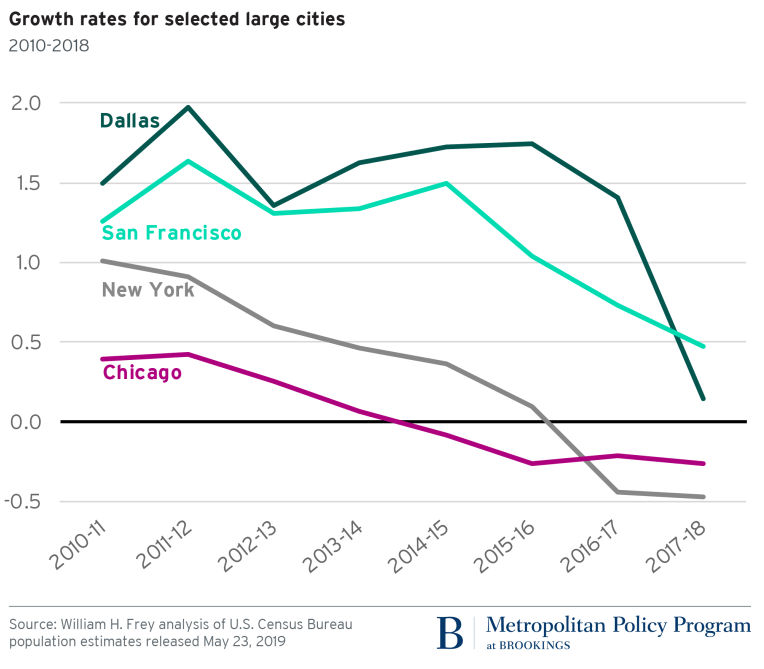

The movement of population into the U.S.’ large cities — particularly the coastal metropolises — that characterized the first decade of the millennium began to reverse in the second.

Now, the pandemic is accelerating that process, for several reasons.

First, urban density has gone from being a blessing to being a liability. It used to facilitate a cultural lifestyle that compensated for the other indignities of city life, especially for Millennials. With the mainstream public narrative now shaped by the threat of viral infection — whether or not that perspective is borne out by the actual data — the city has become an imaginal plague zone, and former enjoyments derived from rubbing shoulders with a diverse and socially stimulating crowd no longer seem so enticing to many.

We mentioned “other indignities of city life.” It’s not just that these indignities no longer have as many attractions to balance them out; the indignities themselves will likely get worse. The most significant of them is taxes.

As a result of the covid shutdown recession, many states and municipalities are faced with fearsome revenue shortfalls and budget deficits; and unlike the Federal government, most of them are required to have balanced budgets. California lawmakers have already proposed raising the state’s top tax bracket to 16.8%. They have also proposed a first-in-the-nation wealth tax, on couples with more than $30 million in assets. The details of this proposed tax are not important; the problem is with the principle. A wealth tax is alarming to proponents of civil liberties for a host of reasons — not least because it implies that all property is held merely at the state’s pleasure, and that it could require affected individuals to furnish the state with a complete schedule of their assets.

But more to the point, as many European countries have discovered, wealth taxes are deeply counterproductive. More than a dozen EU nations used to have wealth taxes; nearly all have repealed them. France’s was repealed in 2017; French authorities calculated that it had resulted in a net loss of €3.5 billion per year because wealthy French citizens simply left the country, and avoided not just the wealth tax, but many other taxes as well. When Sweden abolished its wealth tax in 2007 — as part of reforms that made the country rather different than some of its American admirers believe — the government noted the chilling effect that the tax had on Swedish entrepreneurs, due to the drying up of local venture capital.

Jurisdictions that go forward with such punitive taxation will eventually learn what Europeans did: it suppresses economic dynamism, entrepreneurial activity, innovation, and job creation. We predict that such jurisdictions will become less desirable residences for everyone — not just the wealthy — as opportunities decline. People will “vote with their feet” and move to jurisdictions that treat them better. And let’s not forget that the pandemic has shown us clearly that for many high-income and creative workers, technology has made it easier than ever for them to live wherever they wish.

Of course, there is never a “sunset provision” for new taxes imposed in the throes of a crisis. Therefore we can be reasonably sure that if the pandemic response includes higher and new taxes, those taxes will remain in place when the pandemic itself has been forgotten.

But let’s go back to city life’s “indignities.” These also include things that are mitigated by the public services that make a city cleaner and safer. But those very public services are also likely to be challenged by constrained state and municipal budgets, as well as by calls to reduce funding for public safety (although we see quite clearly the need for intelligent police reform).

New York’s fiscal crisis in the 1970s corresponded to the zenith of that city’s then-deserved reputation for crime and filth (not that we take issue with the fierce loyalty of New Yorkers who loved their city even in its time of trial). It took the city decades to climb out of that ditch. In the words of a third-generation New York real estate developer, “Never forget that New York can be a bad place.” If the pandemic’s economic impact results in a decline in services, that will intensify the flight to states and municipalities where people can reliably find the services they need for a desirable lifestyle. With the oldest Millennials now reaching the “nesting age” of family formation, there may be a perfect storm coming for their coastal citadels.

Investment implications: The population movement from fiscally challenged cities and states, if it is enduring, will have significant effects on quality of life and real estate values — both in the places that are declining in desirability, and in the places that are attracting new residents. While we may be right in our view that the healthcare dimension of the pandemic is proving to be more tractable than the mainstream believes, the second- and third-order effects can still lead to profound shifts.