Until the pandemic broke last spring, all eyes were on the yield curve — the spread between short and long-term interest rates. The inversion of that curve is thought to augur the approaching end of a period of economic expansion. When long term (usually ten-year) rates drop below short term (usually two-year) rates, a recession is statistically two or three years in the future — sometimes much more, sometimes much less. (Thus, this indicator taken in isolation is of limited utility for investors.)

That inversion happened in the latter half of 2019 — exactly when depends on which short-term rate you’re looking at. When it happened, many investors and strategists began talking about starting their recession countdown clocks. A few months later, the arrival of the pandemic and the recession created by the lockdowns imposed in response to it was a coincidence, and had nothing to do with that inversion. The pandemic, the economic shutdown, and the monetary response to the pandemic served to replace any concerns about the yield curve from investors’ minds.

Now, the shape of the curve is getting attention again — but this time, not because it’s inverting, but because it’s steepening — that is, long-term rates are rising faster than short-term rates.

What does this imply? Foremost, that investors are beginning to anticipate inflation and bake it into the prices they are willing to pay for bonds. This expectation of inflation is shown by a number of other trends, such as rising breakevens (the difference between bonds’ nominal and real, i.e. inflation-adjusted, returns).

Whether or not higher rates is a good thing depends on where that inflation is coming from… and the slope of their rise. We could say simply that the steepening curve is bullish for stocks — until it isn’t.

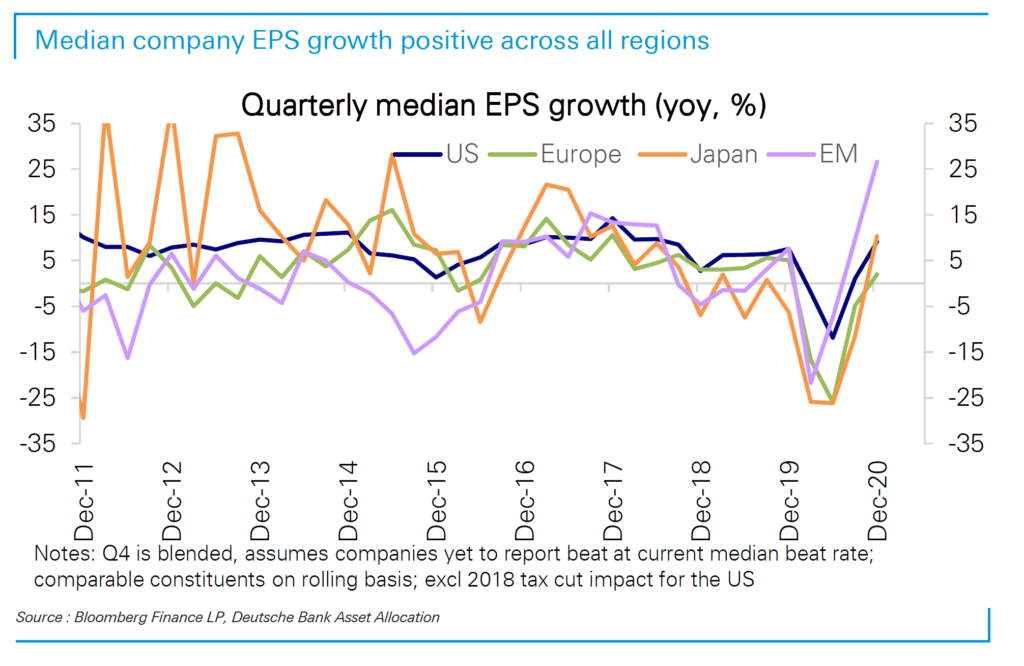

Earnings season for U.S. companies has been extremely strong, and not just in terms of companies beating expectations. “Expectations” are largely a game of careful management by corporate CFOs and Wall Street analysts. Earnings are finally back to growing in absolute terms for the first time since the pandemic broke, and we haven’t lapped the corona-crash yet. That is an indication of strong recovery from the lockdown recession.

Further, with vaccinations proceeding apace in economies around the world, analysts are at least sighting an “all clear” on the horizon and a tentative return to normal at least as far as consumption and mobility are concerned, though many side-effects of the lockdowns will linger and some will be enduring.

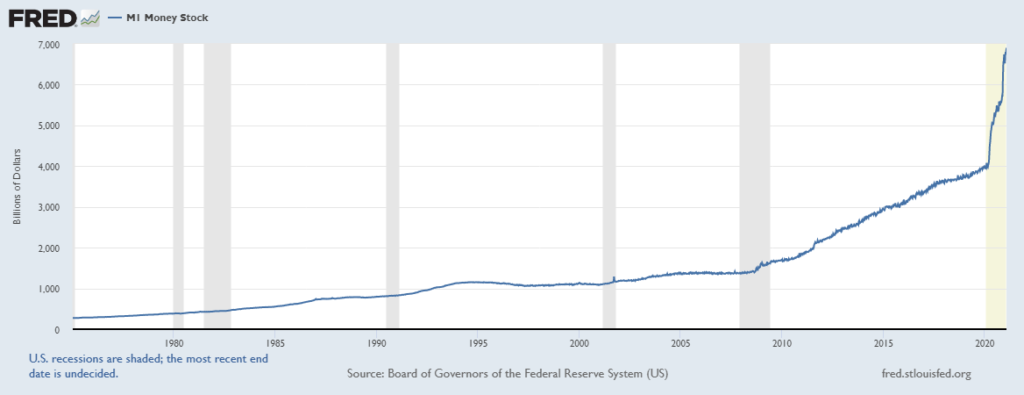

And finally, of course, is the story we’ve been observing for coming up on a year — a wave of liquidity so large that to call it “unprecedented” sounds a little anemic. Nothing close to it has been seen in the history of modern finance.

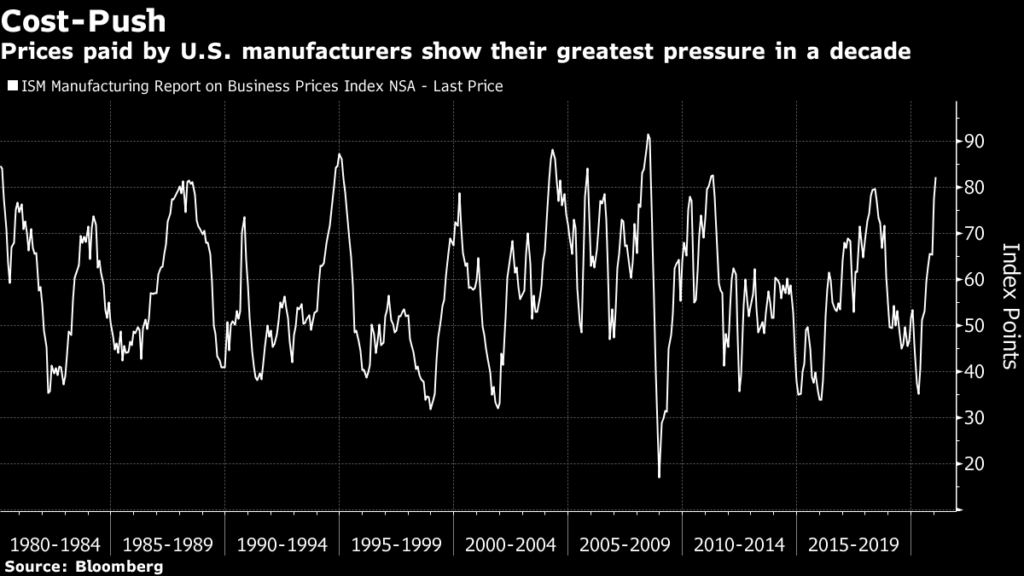

As we have also pointed out since the beginning of the year, a financial Rubicon was crossed during April’s coordinated Fed and Treasury pandemic response last year — the enlistment of commercial banks into the money-creation flood, via loan backstops and forgiveness. We believe this change presages a new phase in post-2008 monetary policy, which is now much more likely to generate broad inflation, since the money created will flow more directly into the pockets of businesses and consumers. Manufacturers are already bidding up the price of materials:

The markets will go from cheering higher rates … to dreading higher rates … and the shift in sentiment can happen fast.

Since rising inflation expectations are a sign of ramping economic activity and an indication of future growth, they’re good from that perspective. Of course, the story is not that simple; they’re good to a point. Part of the reason that the high-growth segments of the stock market have performed so strongly since the Fed and Treasury armies crossed the Rubicon back in April is that growth and inflation have been in question, and the future has been highly uncertain. That has raised the premium that investors are willing to pay for growth (something visible also in the extremely high demand for the lowest-rated segments of the high-yield bond market). Once growth returns more broadly, and when fixed-income returns rise, investors will no longer be willing to pay such a premium, and the price-to-earnings multiples will fall — more dramatically as the stocks in question have risen more dramatically.

Many of the high-growth favorites of the pandemic rally are a far cry from the profitless, businessless wonders of the dotcom bubble. They are real businesses with real prospects and real earnings, and often compelling technological stories to tell that situate them in the epicenter of significant global social, technological, and macroeconomic themes. When the time comes, though, and rising inflation pushes long-term rates above some real but unknown threshold, investors will rethink what that growth is worth, and the result could be painful for the unprepared. We do not know what that threshold is, and neither does anyone else — the best and most realistic analysts really just have observed data and rules of thumb. We have long experience with this type of economic transition, and we are excited to see all the new technologies and productivity-enhancing opportunities being embraced by businesses in every aspect of modern commerce.

In the meantime, investors are correct to be watching inflation and rates — both absolute levels, and the rate at which they are changing. We noted in recent letters that we are likely entering a period of financial repression, given the high indebtedness of developed economies. That means that governments will be unable to tolerate high and rapidly rising interest rates, and will act to repress those rates, even in the face of rising inflation. That’s the broad picture of the financial landscape that seems to be unfolding, but it doesn’t preclude periods in which rates rise sharply before policymakers respond. In the early stages, before for example the explicit implementation of yield caps and yield curve control, such periods seem likely, and coming at the end of a period of blow-off exuberance, they will be sobering.

Investment implications: Much of the world is currently enjoying a strong bull market for stocks. The U.S. and much of developed Asia, as well as parts of Latin America and Europe, are moving ahead nicely. For many of our clients, we are participating in some of the themes and companies benefitting the most from current exuberance, but we find it difficult to recommend them to readers without the caveat that they should be watchful, as we are with out clients, given the precipitous climb of some stocks and industries.

While the market is running, “fear of missing out” will cause most investors to want to participate, since bull markets typically deliver some of their most dramatic returns in their final, blowoff phases. These phases can often endure for longer than the worried consensus believes, as was the case in the bull market that closed the 1990s. Given the potent stimulus emanating from the Fed and from Congress, with only a few lonely partisans of sobriety to be found on Capitol Hill, we would not be surprised if the current bull market had longer to run. But we have our eyes fixed closely on inflation, rates, and policy. These will be the determining factors for when the markets will top.