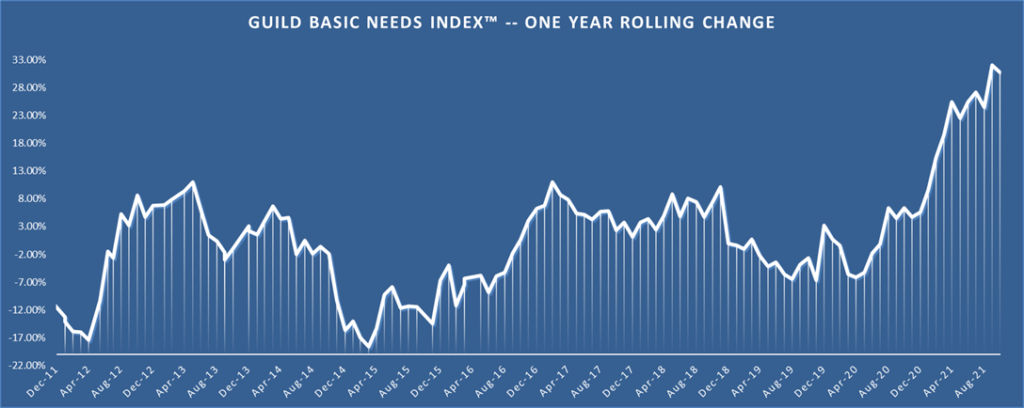

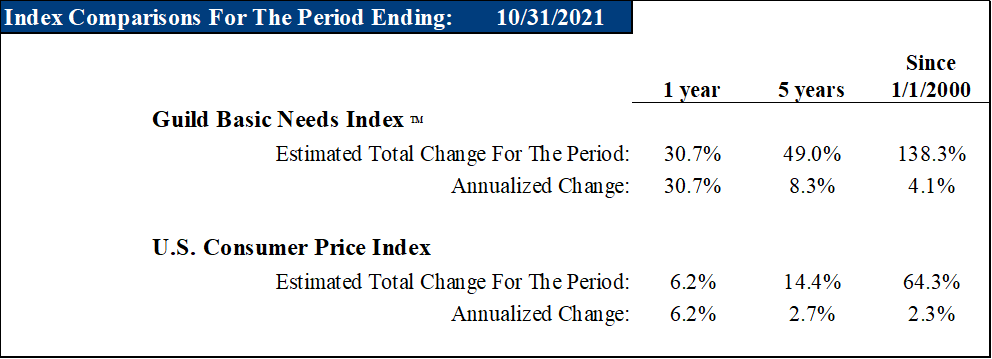

We noted last week that we’d provide you with October data on our in-house real-world inflation measure, the Guild Basic Needs Index (GBNI). Here it is: up 30.7% year-on-year. (The GBNI is constructed to reflect the price of essential living expenditures, without statistical manipulation or adjustment. For more details about the index and its components, see here.)

The debate about whether this inflation is transitory, or whether it will be more lasting, is largely over among independent analysts and economists. The prevailing view is that it will not be transitory.

The reason for that is gradually becoming clear. An inflation spike is typically attributed to a demand shock (demand rising too fast for available supply) or a supply shock (supply suddenly contracting). The presupposition behind the “transitory” theory of our current inflation spike is that it was a supply shock — caused by the sudden shuttering of goods and services production and distribution during the pandemic lockdowns. That, officials reasoned, would resolve itself as the supply chain reopened and the kinks and bottlenecks were worked out. From this perspective, port congestion and trucker shortages, for example, would be irritants that might last a few months — or even a year — but would not create longer-term problems.

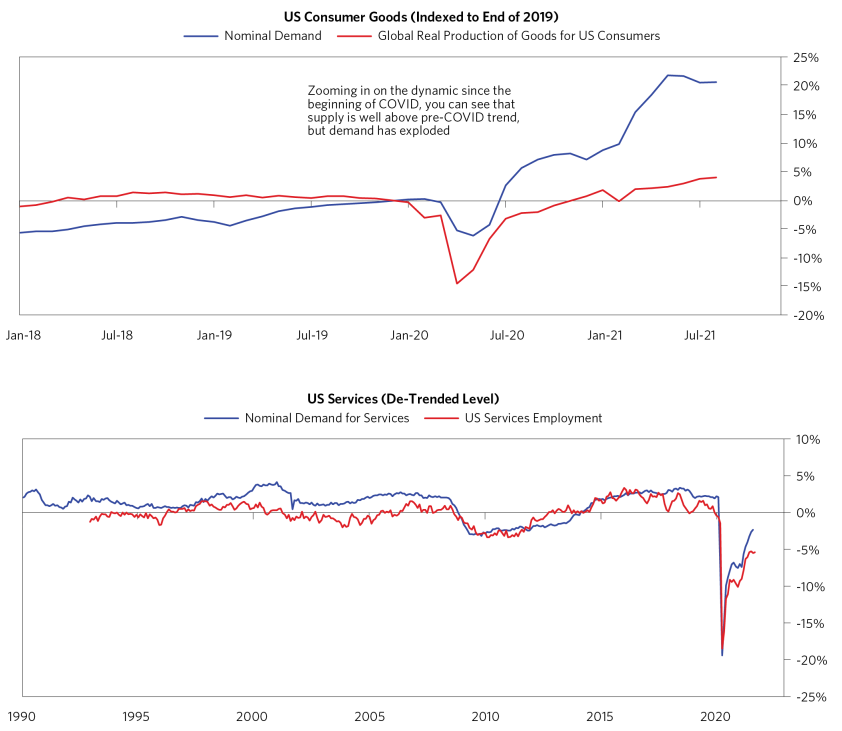

Unfortunately, the evidence suggests that our current inflation spike is not primarily a supply issue. The issue is a massive surge in demand. Supply can’t keep up — across goods and services alike.

Source: Bridgewater Associates

The same is true across many raw materials. Materials vary in the speed with which supply can ramp up in response to demand; for many of them, however, supply expansion requires long-term capital expenditures which have been insufficient for many years already. Metals, in particular, also show that supply is simply not rising as fast as demand. The same is true for energy. The same is true for inventory and shipping capacity. The same is true for housing.

Indeed, the same is true for labor. As we noted last week, the pandemic has pulled forward retirements, though there are many factors operative here — including perhaps a wealth effect from investment gains and cryptocurrency windfalls, as well as a reassessment of workers’ willingness to engage in customer-facing work when pandemic fears are still abroad. Frankly, also, the civility of the general population has reached such a point of decay that we can imagine many consumer-facing workers in retail or hospitality would be eager to exchange those jobs for something “remote,” if they could — and across the board, workers are quitting their current jobs at the highest rate in the data’s history: 4.4 million in September, or nearly three precent of the workforce. There is too much demand for labor, and not enough supply. Hence, at least nominally, wages are rising faster than for many years — even if inflation is stealing that growth.

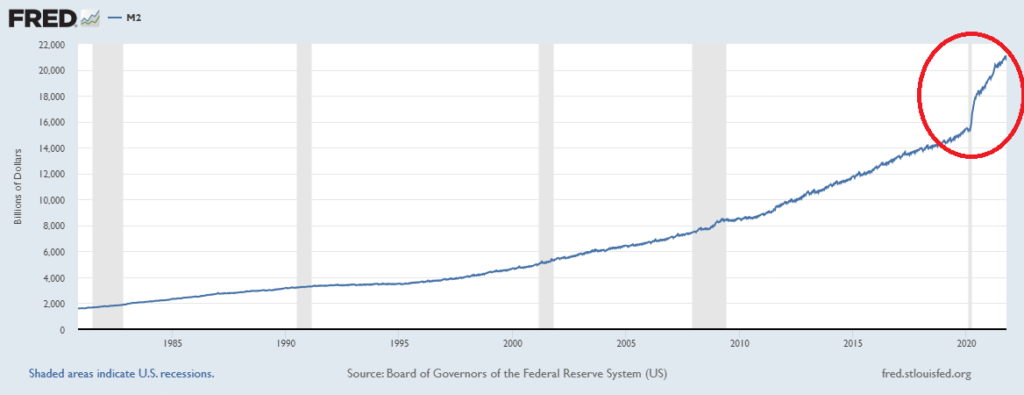

The real question is, Why is demand outpacing supply growth?

It is not a difficult question to answer. Tongue-in-cheek, it takes only one money supply graph: the one showing that 20% of all dollars currently in circulation were created in the last year and a half:

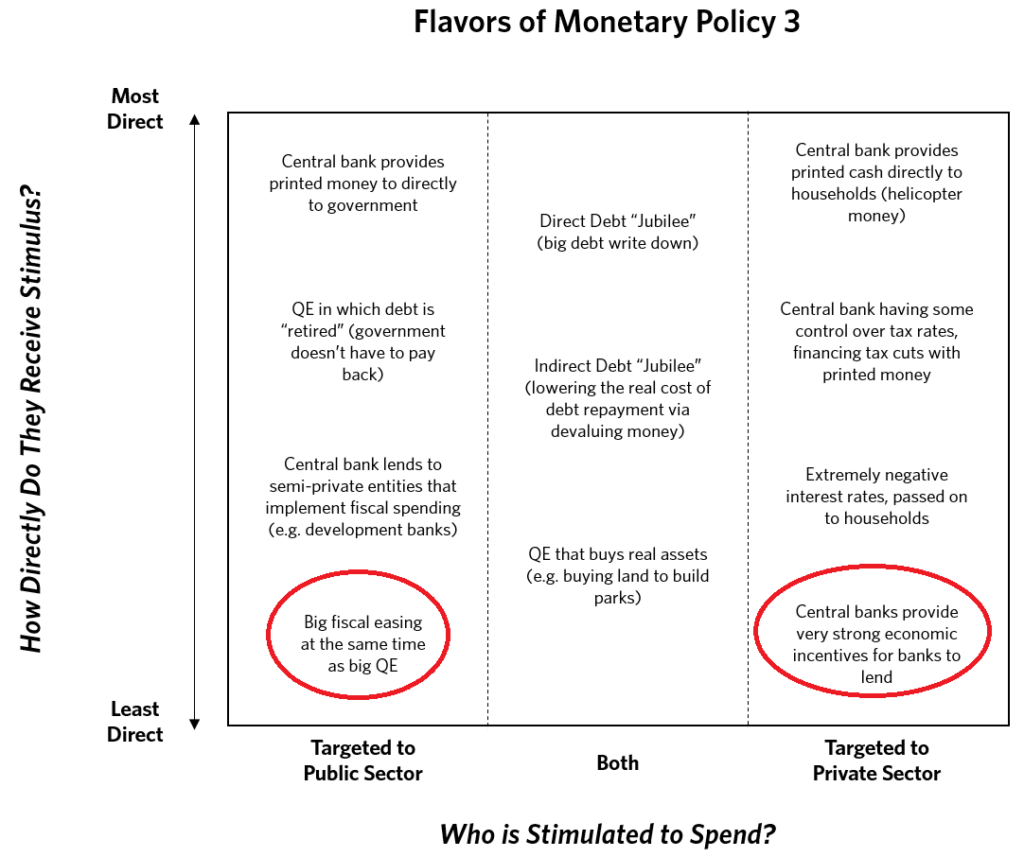

“Toto, we aren’t in Kansas anymore.” We have moved to a new stage of monetary and fiscal policy.

Traditionally, the monetary policy available to central banks was the control of very short-term interest rates. When the Great Financial Crisis hit, that policy proved insufficient, and was radically changed to incorporate quantitative easing and huge central bank asset purchases. Finally, as we have pointed out previously, in April 2020, the covid pandemic response once again crossed a Rubicon, with expansionary fiscal policy, central bank underwriting of corporate bond and commercial paper markets, and more or less open debt monetization.

These shifts mark the entry of fiscal and monetary policy into the same territory as modern monetary theory (MMT). (As you probably can guess, to us, advocating for, or approving of MMT is destructive. MMT is an inflation-creating policy which undermines the standard of living of the lower and middle income public by creating and extending the kind of price rises that damage those income sectors’ ability to save and meet their essential needs. To those receiving it, it creates the illusion of wealth.)

Many have pointed this out, but Ray Dalio of Bridgewater Associates refers to this world as “monetary policy three,” meaning the successor to traditional monetary policy, and Financial Crisis era QE. Here is a chart prepared by them which outlines various policy scenarios. We’ve circled in red the ones that have occurred during the pandemic.

QE, as a policy response targeted to a financial crisis, and intended to bolster a collapsing credit system, failed to generate widespread inflation in the decade after the 2008 crisis because it did not spur demand for very much except financial assets. But that QE was deployed into a collapsing credit black hole of epic gravitational strength, and in the context of a relatively restrained fiscal policy.

The covid-era pandemic “MMT lite” — with unprecedented multi-trillion dollar deficits occurring during ongoing supernova-tier QE, and cash handed out in buckets to individuals and corporates — marked a radical departure. For many months, we have been arguing that this would mean inflation with a vengeance, since those dollars would be spent to fuel demand for more things than just financial assets. That’s what is coming to pass. Demand is rising because huge amounts of dollars were created and injected into the economy in a way that would ensure they got used to express demand for goods and services.

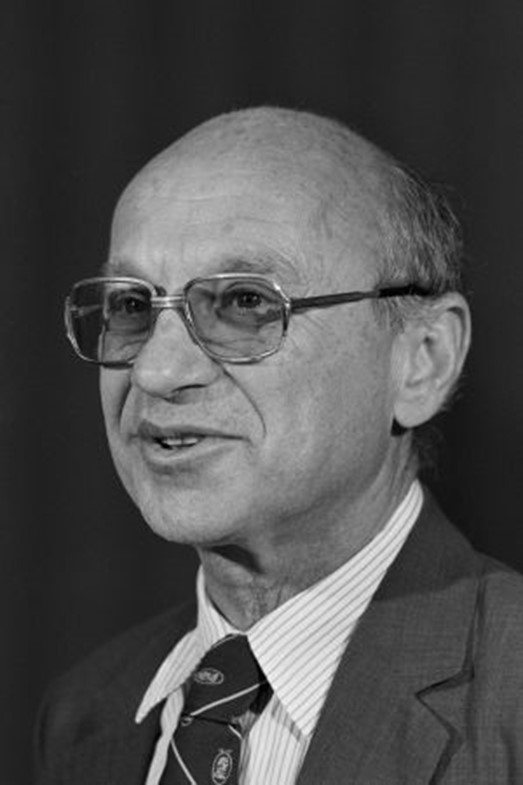

Then-candidate Joe Biden commented in April, 2020 that “Milton Friedman isn’t running the show anymore.” But we beg to differ. What is unfolding shows that the august economist’s observations — that inflation is a “hidden tax,” “taxation without representation,” and “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” — are as true as they ever were. We posit that it would be better if someone with Mr. Friedman’s understanding of cause-and-effect relationships in economics were “running the show.”

Mr Friedman Has Not Left the Room

What has been kicked off is likely the beginning of further waves of inflationary pressures — especially as services demand keeps normalizing as covid fears recede further. Inflation expectations will begin to get incorporated into wage increases, and as Bridgewater notes, “Inflation will become increasingly self-reinforcing, with no easy way out.”

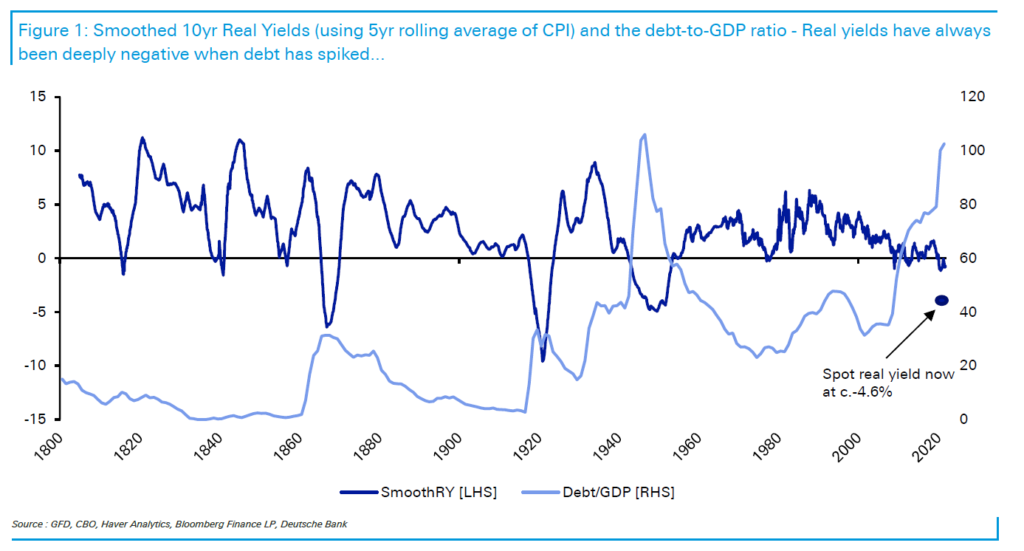

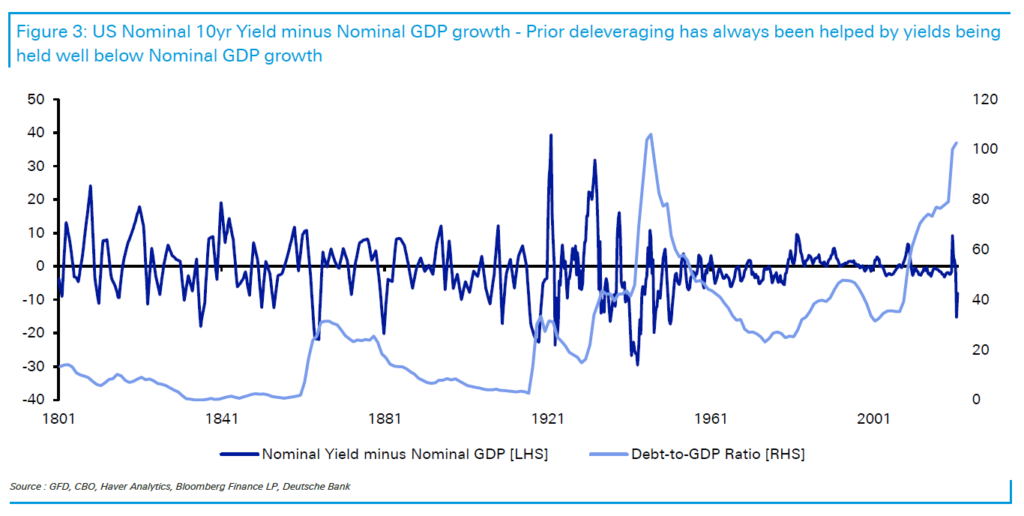

As we noted earlier this year, we do not believe that highly indebted governments who have embarked on this new form of monetary and fiscal policy will be able to tolerate high real interest rates. Various forms of financial repression currently are and will continue to be employed to keep real long-term rates low or negative.

This will not be new; it has happened previously after debt binges. As the charts below show, historical debt-spike episodes have seen deeply negative real rates and nominal rates held well below nominal GDP growth.

Source: Deutsche Bank Research

Investment implications: Inflation is running hot — much hotter for essential consumer goods than suggested by official CPI numbers. It is becoming clear that this will be more persistent, and not just a transitory phenomenon — driven mainly by a demand shock rather than a supply shock, and likely to escalate as wage increases get baked into the economic pie. On the other hand, we do not see central banks in a position to allow long-term real rates to rise uncontrollably, nor does history show that this will occur following a debt binge. On balance, therefore, the persistent demand-shock driven inflation we see unfolding is likely to favor inflation hedges, growth stocks, and other long-dated assets whose pricing depends on interest rates — as well as gold and cryptocurrencies. Of course, we also see the likelihood of elevated volatility.