In each earnings season, banks are among the first to report and help set the tone for what investors expect moving forward. We already knew that the second quarter of 2020 was going to be an earnings apocalypse — so much so that the quarter itself is largely irrelevant for many companies. The important thing is what managements have to say about their views of the rest of the year and 2021 — if not formal guidance, at least their impressions. In a situation of remarkable uncertainty, investors are starved for actionable signals.

Many banks reported and the news was decidedly mixed. On one hand, revenues for the banks with big trading operations were stellar — as one would expect in an environment of crashing and rebounding stock markets and record debt issuance by central banks and corporates. On the other hand, the six biggest U.S. banks added about $36 billion to their reserves for future loan losses. From a year ago, JPMorgan [NYSE: JPM] increased its provision for loan losses by 143%. JPM’s CEO, Jamie Dimon, regarded by many as a bellwether financial commentator, said: “This is not a normal recession. The recessionary part of this you’re going to see down the road.” JPM’s CFO, Jennifer Piepszak, added, “May and June will prove to be the easy months in terms of this recovery, and now we’re really hitting the moment of truth I think in the months ahead.”

Clearly, the U.S.’ major banks are expecting some severe economic fallout from the “coronacession” before all is said and done. JPM’s loss provisions are in line with its fairly dismal economic view of the rest of 2020 and 2021. The company’s economists now expect U.S. GDP to contract 6.6% in the fourth quarter of 2020, and 3% in full-year 2021. So much for a V-shaped recovery, according to JPM.

The bank emphasized the uncertainty of the environment, with which we can certainly concur. So far, retail sales have rebounded strongly from pandemic lows; however, much of that rebound was fueled by stimulus checks and Federal unemployment supplements; those enhanced benefits are scheduled to expire on July 31, with contentious negotiations looming ahead of any extension or renewal. Is the V-shaped recovery the artifact of a novel experiment in “universal income” stimulus to the economy’s bottom 50% — and will it stall when that experiment is ratcheted back?

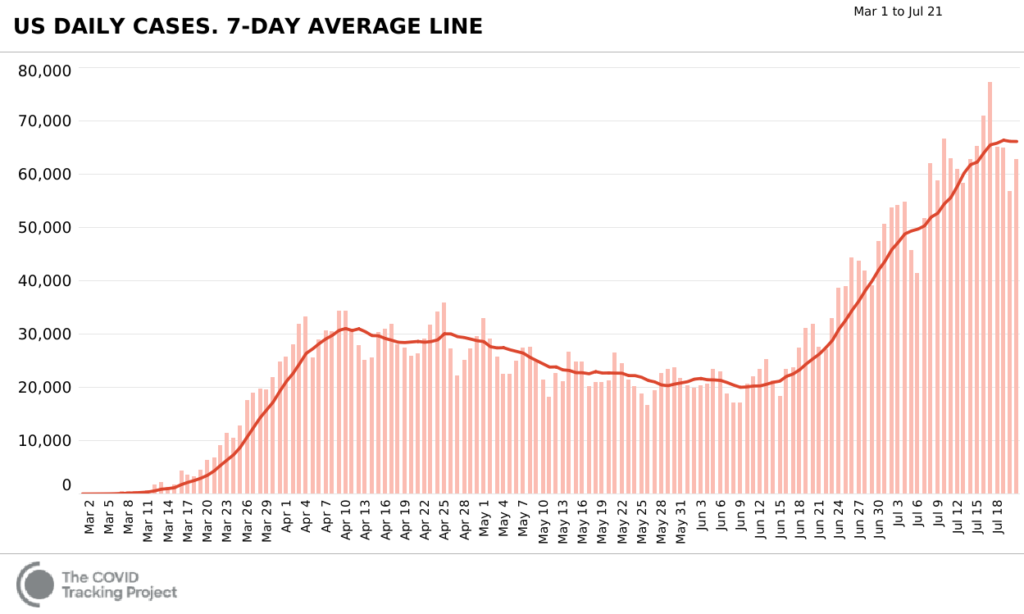

Then, there is the ongoing process of the pandemic itself. Headlines continue to focus on the rapid increase in positive tests:

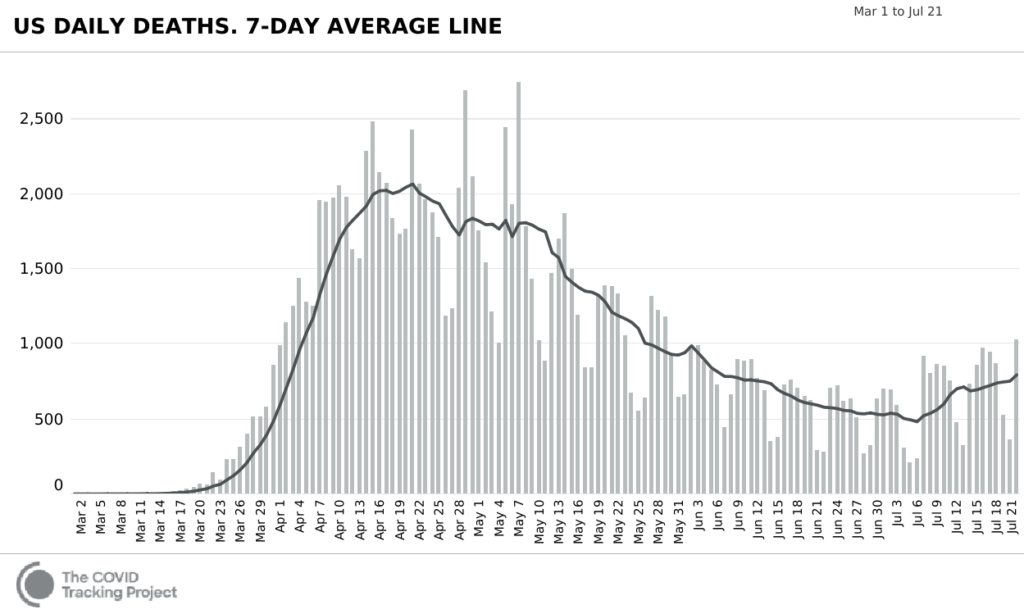

Despite widescale reopening, lack of social distancing measures during protests, etc., daily deaths, while showing an uptrend, remain relatively subdued:

Even more significant, and not adequately reported, is that according to the COVID Tracking Project, nationwide, ICUs are not overwhelmed, and the number of patients receiving ICU care is growing quite slowly, and remains far below the April peak. (Remember also that as April demonstrated, ICU capacity is not static, but can be expanded fairly rapidly when necessary – for example, by the transfer of non-ICU patients to neighboring hospitals and the reallocation of beds.)

JPM and the other banks, however, seem to be focused on the potential risk of longer-term economic trouble in the future for energy, airlines, and other suffering industries where banks have outstanding loans and the risk of these loans going sour. Many of the fast-growing industries that investors favor have light bank borrowing, while many of the old-economy industries where banks have loans are disadvantaged by current and expected economic trends.

But Here’s What Matters More

We think the observable dynamics of the pandemic, beneath the headlines, do not justify the level of general economic anxiety. Of course, that anxiety relates not just to what the effects of the pandemic will be, but to the effects of further government-mandated economic closures. We know that, to put it politely, governments do not always act with full rationality and occasionally have ulterior motives. We know that, to put it politely, governments do not always act with full rationality and occasionally have ulterior motives.

However, we do not believe that the majority of the population, and the majority of pragmatic, grassroots level officials, will tolerate another round of severe shutdown measures, unless there is a radical shift in mortality and ICU trends. There may be milder “stay at home” measures re-implemented, but not on the scale seen in April and May, and with less impact. Therefore, we side with those who are more optimistic about the prospects for economic recovery.

We also think that politicians on both sides of the aisle, even in the run-up to a bitter election season, will get a further stimulus bill through, because everybody’s constituents want it.

But the main thing is simply the liquidity. This is the monstrous energy driving the stock market rally since the March lows, and there is more to come. A staggering amount of liquidity has been injected into the global financial system — not just through central bank monetary stimulus, but through fiscal stimulus coming from new government and especially corporate debt.

The Institute for International Finance — a trade group of hundreds of the world’s largest banks — noted in a recent report:

“The corporate sector accounted for over 65% of the rise in the global debt-to-GDP ratio in Q1 2020… Looking ahead, we expect the rise in corporate debt to continue at an accelerated pace. With abundant central bank liquidity, the decline in borrowing costs for corporates has already led to a substantial surge in corporate bond and loan issuance since March, amounting to some $4.6 trillion in Q2—vs a quarterly average of $2.8 trillion in 2019.”

That trend is worldwide:

Investment implications: We invite readers to consider that the following scenario has supportive evidence and a reasonable likelihood of proving true:

- that the U.S. and global economies are stronger than many believe;

- that the pandemic is more likely to be controlled without further disruptive closures than many think;

- that epochal levels of liquidity have been created in the global financial system through fiscal and monetary expansion;

- and that much of that liquidity remains on the sidelines.

These factors could mean that the current phase of market exuberance, with volatility and the risk of occasional corrections, has further to go. In our view, the long-term consequences of this liquidity surge argue for an allocation to gold and silver.