The tumult of countervailing forces at work in the global economy, and besetting investors, increases in strength day by day.

Last week we wrote extensively on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and its implications for a host of global financial and commodity markets. The invasion itself surprised many seasoned analysts who believed that Vladimir Putin was bluffing; the progress of the invasion also surprised many who had believed that an outgunned and relatively disorganized Ukrainian military would quickly fold and that the country would fall. Instead, aided by a fair amount of grit, Stinger and Javelin missiles, and soon drones, Ukraine has managed to stall the broad Russian advance.

Moving forward, predictions of the war’s outcome should evoke humility from even the most knowledgeable. The most we can do is trace out some possible trajectories, and evaluate their likely effects. The same goes for divining the outcome of the global geopolitical shifts that are now underway as a result of the sanctions imposed on Russia by western governments and corporates (though notably, not by India or China).

Neverending Sanctions

It is possible that the war concludes quickly with a Russian victory, which would leave Europe in a particularly difficult position, as there would be no justification to dial back sanctions and ease the flow of critical energy and materials from Russia. If the war did not conclude quickly, but became a protracted guerrilla conflict, that would spell even more trouble for Europe, and indeed, for the rest of the world. With Ukraine embroiled and Russia embargoed, many critical commodities, from nickel to wheat, would experience sharp inflation and volatility.

The potential ramifications are wide — from counterparty failures in leveraged commodity markets and their financial intermediaries, to unrest in developing countries. We recently read a comment that “Even in Egypt, they bake their bread with Ukrainian wheat,” and there is unlikely to be a planting season this year. Sharp food price spikes spell trouble in many such parts of the world, with unforeaseeable downstream effects on global geopolitics.

Europe In the Crosshairs

We suspect that Europe will fare particularly poorly however the war unfolds. That in turn suggests relative strength for the U.S. dollar, as European wealth seeks to find a home in dollar-denominated assets. Such a flow into dollars could help constrain rising prices (and thereby interest rates) in the United States, even as the Federal Reserve begins what it has now more or less plainly declared will be a long series of hikes stretching out to the end of 2023, where the dot plot forecasts suggest a 2.8% Federal funds rate.

The Weaponization of Currencies and Trade

The fate of the ruble and of Russia’s relationship with the western economic and financial system suggests that evaluating currencies now requires a more significant qualitative analysis — it’s not just a matter of reserves, trade balances, and debt-to-GDP ratios; if those were all that mattered, the ruble would be a buy. The freezing of Russia’s reserves represents a weaponization of the global monetary system which will contribute to a more multipolar monetary world in coming years. We don’t believe this yet constitutes an existential challenge for the dollar, given the unsuitability of the ruble or yuan to serve as a global reserve. The flows will tell whether and how quickly that shifts

We see little or no risk that the US dollar becomes less important in the world economic system as a result of this war. There will be bilateral trade between Russia and China and Russia and others. Big deal bilateral trade does not impact the strength of the global reserve currency.

, but we believe it will be a matter of decades before multipolarity really gains traction — if at all. Still, the changes are significant and could be harbingers, and are therefore worth watching — although not worth reacting to prematurely.

Recession

We believe that recession risk is high in Europe; the seriousness of this recession will depend on the progress and resolution of the war. Recession risk is also rising in the United States. Clarity about the Fed’s forward path has resulted in a relief rally, but our position is still cautious. Commodities have rallied strongly due to the war and rising inflation, but recession will be bad for commodity prices and commodity producers.

On the other hand, times like these — with global uncertainty, volatile events, a wide dispersion of possible outcomes, and tectonic shifts in global financial and trade relationships — are the times when governments accumulate gold. Russia will likely be a seller — if it can — but that will not, we believe, be likely to significantly dent aggregate demand.

Chaos At the London Metals Exchange

The chaos that unfolded on the London Metals Exchange (LME) as nickel exploded with the arrival of Russian sanctions was interesting and instructive. It is important for American retail investors to understand how much of a “Wild West” such commodity markets are. The LME froze nickel trading and then reversed overnight trades in a way that seemed to favor exchange insiders — in particular a large Chinese nickel company. The LME is owned by Hong Kong based Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing, and is now accused of favoritism. Algorithms are not as capable of evaluating this kind of risk — so developments of this kind are an argument for active management by human managers who can evaluate risks intelligently and qualitatively.

If you think that this problem can only afflict commodities traders, we note that two popular exchange-traded products from Barclays were recently suspended from new share issuance and redemptions after high demand broke their capacity to handle such sale and issuance of new shares. Investors tempted to trade in commodity volatility should beware using instruments which may be pulled from underneath them at an inopportune time (read: likely at the worst possible moment).

Inflation

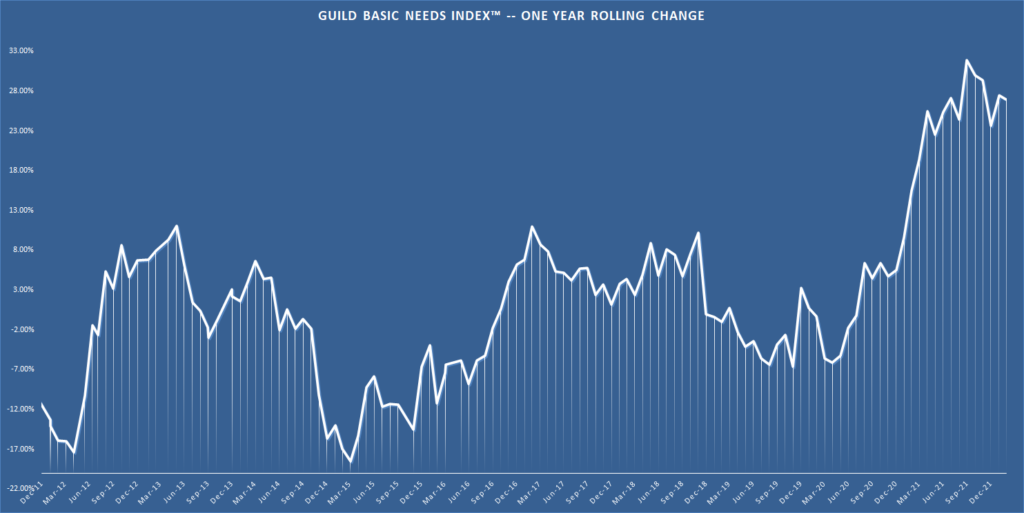

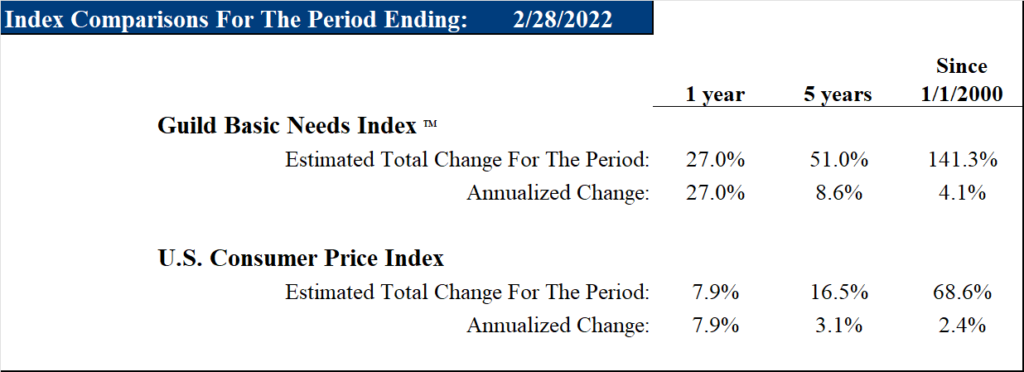

Although we’re waiting for data on housing prices that will be released tomorrow, we’ll provide you a small teaser of our in-house real-world inflation index, the Guild Basic Needs Index, which attempts to measure the costs of basic and essential goods that U.S. consumers experience on the ground. Pending the housing data, our inflation index stands at a 27% year-over-year rate — off the post-pandemic highs, but remaining elevated — and well above the Consumer Price Index. That explains why as you buy food, clothing, and fuel, and pay your rent, something seems quite a bit worse than CPI would suggest.

We’ll check in again next week with the final numbers.