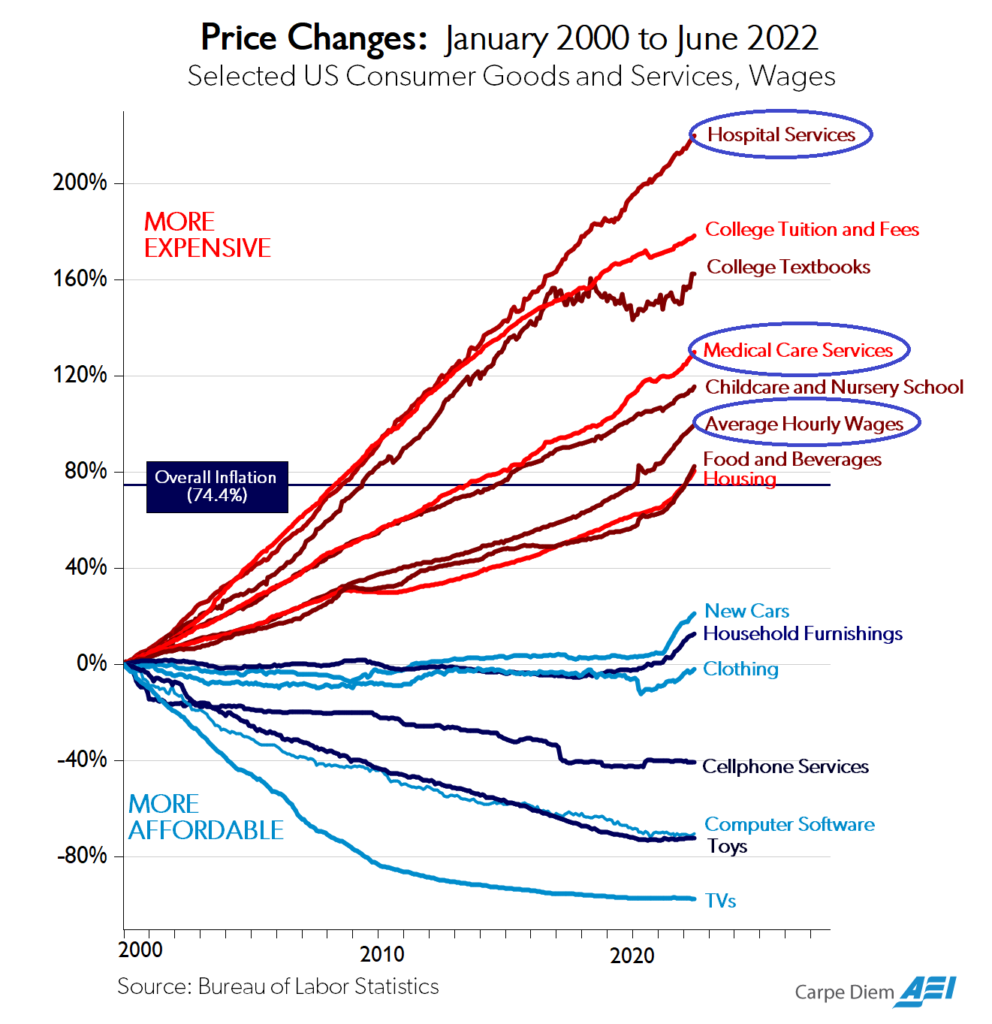

You have probably seen many graphs like the one below, illustrating the inexorable rising cost of healthcare to the American consumer. Given how much healthcare has outstripped the price increases for other categories, how much it has outstripped wage gains, and how important health care is as a necessity of life, many readers have asked us why we do not include healthcare in our calculation of the Guild Basic Needs Index [GBNI].

Source: American Enterprise Institute

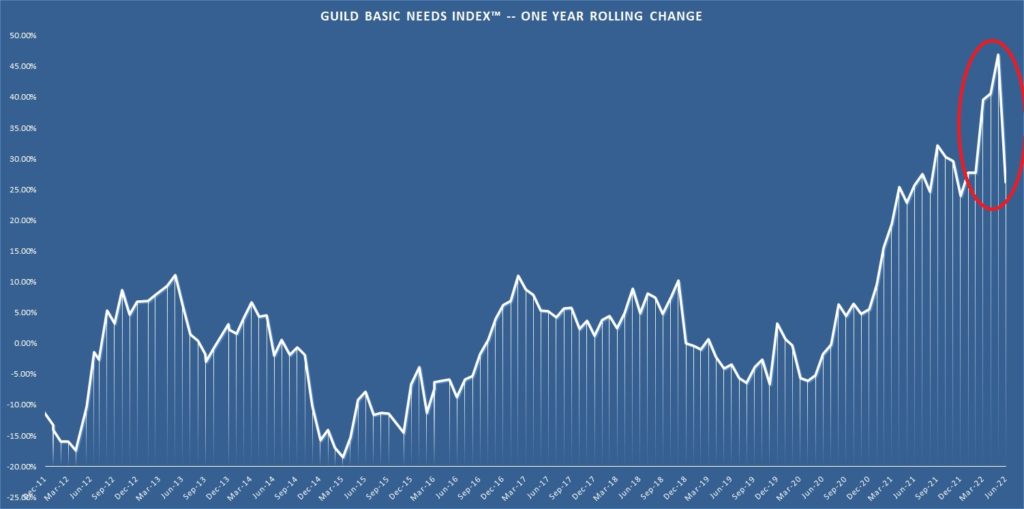

Our regular readers will remember that the GBNI is a simple, constantly weighted index intended to capture the real inflation felt by real consumers for the real essentials of life. This consistent and clear index is opposed to the complex, ever-changing, statistical sleight-of-hand of indexes such as the CPI and CPE, which can serve to conceal the realities of inflation from the public through academic sophistry.

The GBNI includes unchanging allocations to clear and objective price indexes, usually based on spot commodity prices, for consumer essentials: food, clothing, transportation, and shelter. As a reminder, while it has retreated from its recent peak, it is still highly elevated — still running above 26% annualized.

Even though healthcare expenses are existentially significant to U.S. consumers, we do not include them for the simple reason that there is no clear, transparent, comprehensive index that can accurate represent these expenditures in a way that meets the goals for the GBNI.

In a sense, “health care expenses” as a category is an abstraction that amalgamates a bewildering variety of highly disparate goods, services, and expenses. Academic economists, and the professionals who construct the healthcare components of official CPI statistics, struggle to incorporate the full panoply of healthcare items in that index in a way that holds quality and composition constant. Indeed, the CPI does not include healthcare insurance premiums because “the CPI has been unable to consistently control for changes in quality such as policy benefits and risk factors.” In short, it is an illusion that health insurance consists of discrete, fungible units which can be consistently and transparently priced (as, for example, we price bushels of hard wheat or barrels of Brent crude on a liquid, transparent spot market).

The CPI also attempts to track out-of-pocket expenditures — but if, for example, a patient visiting a doctor makes a $20 copay, and the physician receives $80 from the insurer, the full $100 is the basis for CPI calculations. In other words, the ones receiving healthcare are rarely the ones paying for it — which is why estimates of consumers’ out-of-pocket expenditures look so different from the healthcare composition of GDP. The opacity of costs; the omnipresence of negotiated deals; the complexity of reimbursement structures; and the head-spinning diversity of actual good and service deliverables make any statistical amalgamation of healthcare costs to the consumer depend on so many arbitrary model-making decisions — that these models lose most of their interpretive value. Real costs to patients and their families also include transportation and opportunity costs from time taken for treatment; payment to care-givers; opportunity costs incurred by unpaid caregivers such as family members; and on the positive side, wages received through sick leave, and disability and other transfer payments.

Finally, we note that although health care is a necessity, its consumption has a lot to do with one’s fortunes, position, and choices. While no one can exclude food or clothing from their consumption basket, many can and do exclude healthcare of their own volition — with eventual catastrophic consequences that sometimes don’t manifest for many years.

All these are the reasons we don’t include healthcare in the GBNI. But we are pretty confident that the broad statistical picture allows us to conclude about healthcare expenditures the same lesson that the GBNI teaches us about consumer expenses in general — they are likely to be growing much faster than the official statistics are telling you.