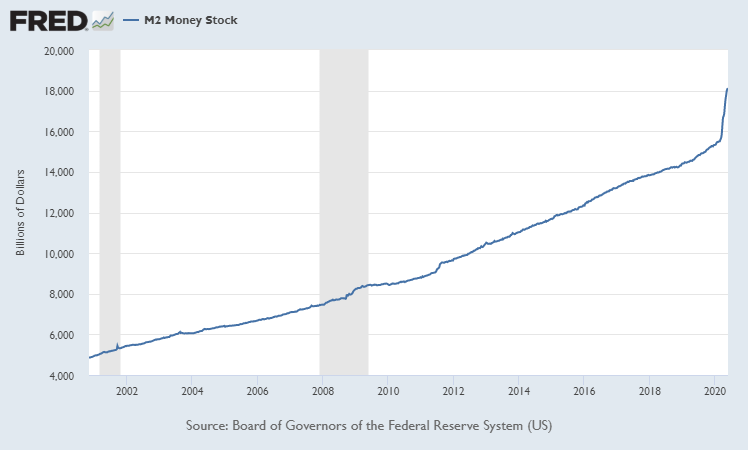

Two weeks ago, we briefly mentioned the worry some investors have that the Fed’s response to the coronacrisis could result in uncontrollable inflation, or even hyperinflation. At first blush, the expansion of M2 visible since the Fed’s crisis stimulus seems to justify the concern:

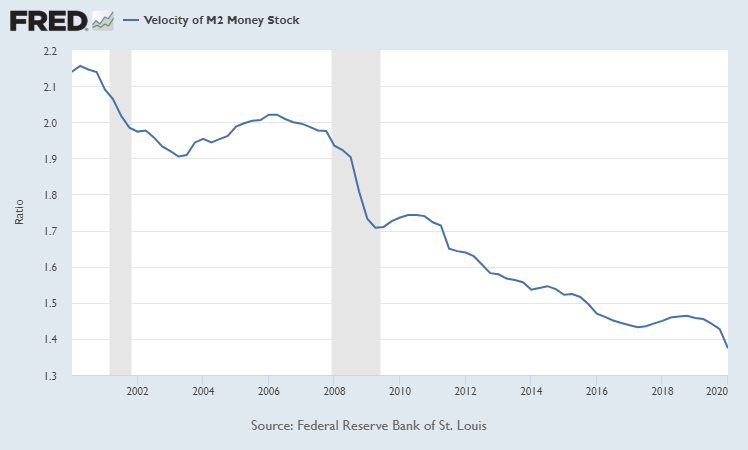

However, while the broad money supply has indeed risen with historic rapidity, we note that the velocity of money, which measures how quickly those dollars change hands, is at historic lows, and falling.

Monetary expansion does not necessarily translate into inflation, of course; a brief reflection on the decade that followed the Great Financial Crisis demonstrates that. Crises are usually disinflationary (causing prices to grow more slowly) or outright deflationary (causing prices to fall).

The coronacrisis presented analysts with a conundrum, because it combined a supply shock (which is inflationary) with a demand shock (which is deflationary). However, it seems clear now that the crisis’ overall effect is indeed significantly deflationary. The money supply is rising; but the velocity of money is falling, and in addition, there are powerful deflationary forces at work blunting the potential inflationary effects of that liquidity. Some of these deflationary forces may be transient, but some may be lasting — and the crisis may well end up intensifying long-term secular deflationary forces that have been at work for decades. Capital markets are not expecting inflation to arrive — indeed, they are implicitly predicting a prolonged period of low inflation.

Further, many structural changes have occurred in the U.S. financial system in the post-2008 period. These changes make it impossible to draw a direct causal link between the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet and the arrival of inflation across the economy (although that balance sheet expansion could be said to have resulted indirectly in “inflation” in financial assets). In order for the Fed’s balance sheet expansion to translate into inflation in the broad economy, the Federal Reserve and the U.S. government will likely need to make a series of policy choices that we do not believe are imminent.

Excess reserves held by banks at the Fed — reserves above and beyond those banks are required to hold by law — have grown enormously since the 2008 crisis, making up a larger and larger part of the liabilities that balance the assets on the Fed’s balance sheet. (In part this is because of the ongoing effects of that crisis in banks’ perception of duration risk with U.S. Treasuries, and counterparty risk in the overnight lending markets.) Since 2008, the Fed has paid interest on those reserves, and setting the rate of interest it pays — the IOER or “Interest on Excess Reserves” — gives the Fed a powerful tool for anchoring short term interest rates in the presence of high excess reserves. In short, if inflation appeared, the Fed would use the tools at its disposal to counteract it — as long as it maintains its mandate, and undue political pressure does not come to bear on it to allow inflation to run rampant.

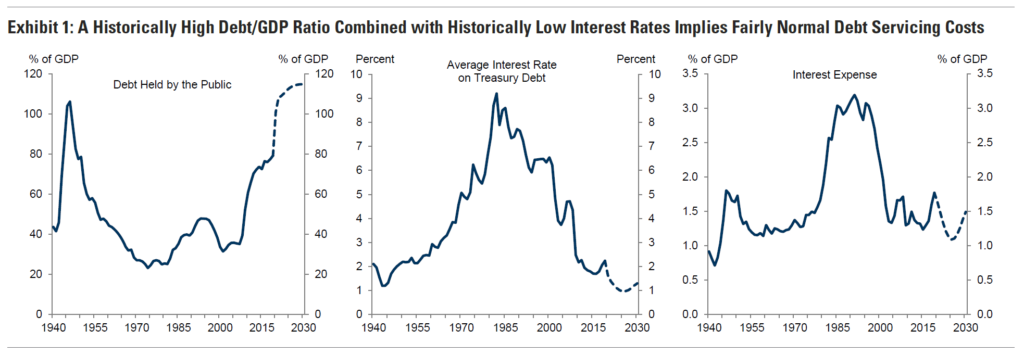

What would cause such political pressure to rise? Even with the debt added by the coronacrisis stimulus, the U.S.’ debt servicing costs are manageable.

Essentially, in order for current policy to result in broad inflation in the economy, we would need to see (1) the reduction of long-term deflationary forces, combined with (2) action from the U.S. government that would respond to rising interest expenses not by cutting spending or raising taxes, but by permitting inflation to rise far above the Fed’s 2–2.5% long-term average target.

We simply believe that both of these factors are unlikely to arrive in the near future.

As a caveat, we note that this is exactly what happened in the year immediately following the Second World War, during which the Fed had adopted yield curve control (which, as we discussed last week, is now very much on the table once again as a Fed tool). Political pressure led to the Fed maintaining that control after it was no longer warranted, and the resulting inflation helped reduce the burden of much of the debt accrued during the war — taking it from 106% of GDP in 1946 to 66% by 1951. (Of course, there were many other factors at work as well — including a government that ran a large primary surplus.) So it is not impossible that a reluctant Fed can allow for inflation overshoot. We simply do not believe it is likely to happen any time soon.

Investment implications: We don’t think inflation, much less hyperinflation, is in the cards in the near future. We believe that the U.S. will be grappling with disinflation for some time. Note that this does not necessarily mean poor performance for gold, which can benefit in both inflationary and disinflationary scenarios; but it does remove some of the more outlandish upside targets for the yellow metal.