Even as the recovery of stock markets from the March and April decline continues and broadens, investors’ attention remains focused on Federal Reserve policy. As we described last week, Fed policy has been instrumental in preserving financial stability, not only in the U.S., but globally. With the initial crisis past, the economy re-opening, and investors looking past 2020 earning to try to discern the trends for 2021, the Fed’s policy is not static. This week we’ll relay some analysis of where the Fed may be headed in the near future. The short version is that the Fed remains committed to do “whatever it takes,” as Chair Powell told 60 Minutes.

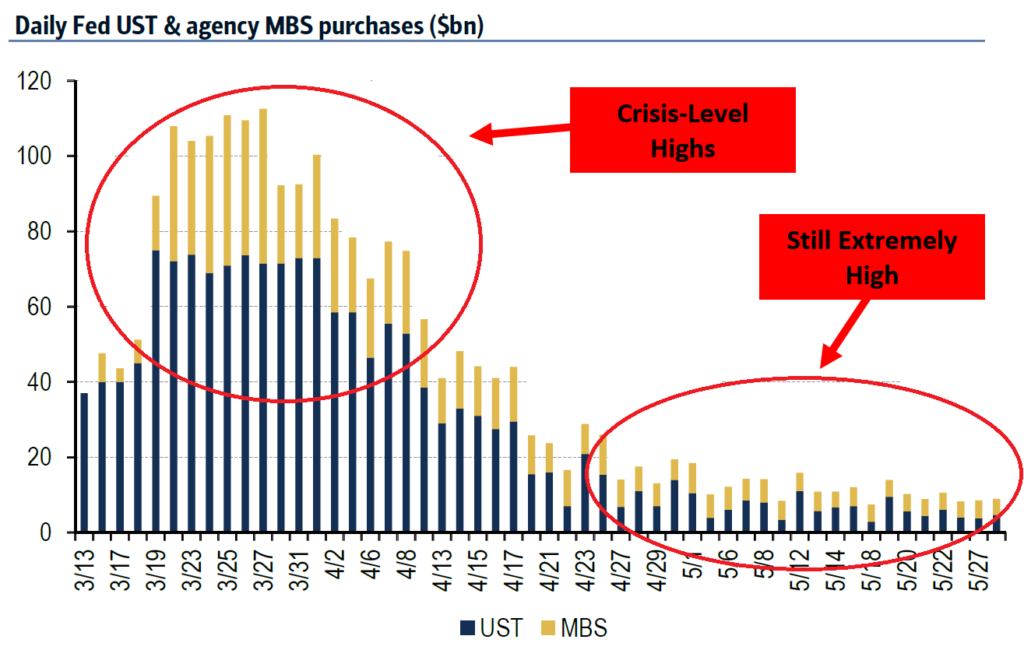

The Fed has already reduced the blistering pace of asset purchases that occurred in late March and the beginning of April.

Based on comments from members of the Fed’s Open Market Committee, how is the Fed’s support for markets likely to look in the near future? Several members have stated that these clarifications are unlikely to come at the June meeting, which conditions remain so uncertain, but they are likely coming soon.

The Pace of Ongoing Asset Purchases

Members indicated that they believed more clarity was in order about the future pace of asset purchases. A very large surge in Treasury supply is coming as the Federal government finances its COVID stimulus programs. Further stimulus is a matter of “what and how much exactly” rather than “if,” so that Treasury supply will continue to be heavy and the Fed will have to absorb much of it to keep the market functioning smoothly. The Fed will likely land at a rate of $80–120 billion of Treasuries and $25-35 billion of mortgage-backed securities per month. The current pace is within these ranges, and FOMC members have said that any changes are “down the road” and not imminent.

Forward Guidance

The Fed said that rates will remain unchanged until “the economy has weathered recent events and is on track to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals.” Some FOMC members want to make that guidance more explicit. “Maximum employment” has previously meant unemployment in the 5% range; that is likely to be closer to 4% moving forward. “Price stability” has previously meant an inflation rate of about 2%; recently there has been discussion of “overshoot,” i.e., a willingness to tolerate higher inflation in the early part of an economic cycle so that the rate will average 2% over the whole cycle. The Fed may or may not embrace that philosophy, but FOMC members have commented on a “hybrid” method which would give a range just for the expansionary period of 2–2.5%.

This combined guidance on unemployment and inflation is likely to mean a more dovish tilt in the future, and prolong the period of accommodative policy. If the Fed formally embraced a definition of “liftoff” — that is, when rates can begin to rise — requiring both characteristics, that would likely mean liftoff is at least several years away.

Yield Curve Control

The most significant change in the Fed’s guidance arsenal may be yield curve control (YCC). This means that rather than simply setting the shortest-term rates, the Fed would set explicit target rates at various durations of the U.S. Treasury yield curve. This policy might become important if the economy strengthened faster than currently expected, and market participants began to doubt the Fed’s willingness to stay the course. By capping Treasury rates out to three or even five years, the Fed would send a powerful signal about its intentions, and anchor market expectations about its future policy. Many FOMC members have made positive comments about YCC recently, and the policy is currently being used in Japan and Australia. The Fed’s May 20 minutes read in part: “A few participants also noted that the balance sheet could… reinforce the Committee’s forward guidance… through purchases of Treasury securities on a scale necessary to keep Treasury yields at short- to medium-term maturities capped at specified levels…”

It is likely that if YCC is implemented, the Fed’s “standard” monthly purchases of Treasuries will shift out to longer durations and provide support there as well — if not explicit targets.

Again, as a reinforcement of forward-looking policy, YCC will likely not be implemented until some time after June, when the Fed’s guidance solidifies — perhaps after their delayed framework review is completed in the fall.

What’s the bottom line? The Fed is in it for the long haul, and the central bank’s determination to keep rates supportive is likely to depend on more basically dovish criteria than obtained in the immediate pre-COVID past. We can look forward to a powerful confluence of monetary and fiscal policy continuing to drive up the money supply at a rapid rate.

Investment implications: Now is not the time to quarrel with the people creating the money. All of this liquidity will go somewhere, and if the past is a guide — and we believe it is — a great deal of it will find its way into financial assets. The long-term ramifications of these policies may be troublesome, but we are far from those long-term consequences. For now, the powerful mechanism of Fed policy and Federal government spending is creating an opportunity for stock investors.