The Real Data Are Weaker Than China Will Admit

China’s rise as an economic power has been good not just for Chinese businesses selling goods to the rest of the world; it has also been good for global businesses selling goods and services to China. Big U.S. companies have been some of the prime beneficiaries, and most of corporate America’s biggest players have established a presence in China — both to manufacture goods there for sale in other markets, and to sell into the Chinese market itself. As trade war tensions have escalated, investors have begun to think hard about the revenues of U.S. companies who sell a lot of goods and services to the People’s Republic, wondering what China might do that could affect their ability to do business there. Businesses themselves have been scrambling to get ahead of changes if they can.

However, it’s not just the trade war that is causing concern for American companies that manufacture in and sell to Chinese markets. The American Chamber of Commerce has had a branch in Shanghai since 1915, and conducts an annual poll of members to provide a picture of their activities, plans, expectations, and concerns. The most recent results were just published and had some interesting food for thought.

Surprisingly, the report highlighted that concern about China’s economic situation is now greater among American businesses in China than concern about trade policy. The report stated:

“A slowing economy was the greatest three- to five-year challenge (57.8%), up by 22.5 percentage points. The new option of U.S.-China tensions ranked second (52.7%), while the previous top two – increasing labor costs and domestic competition – both saw large declines (down 17.5% and 11.8%, respectively). Evidently the business community is more concerned with macro issues such as economic conditions and international trade relations than quotidian issues such as labor costs, domestic competition and local policies.”

It’s not surprising to us that U.S. businesses in China are concerned about trade policy issues. It’s more interesting that their top concern is the slowdown in the Chinese economy.

The Chinese Economy Matters

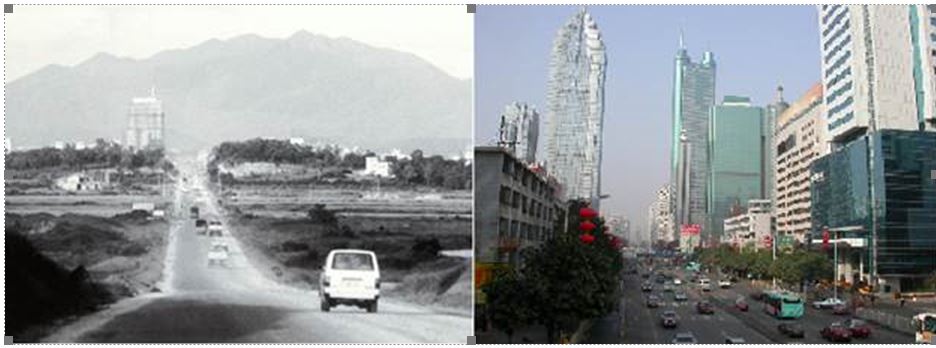

This concern highlights a reality of the contemporary world: China matters. Many events have occurred over the past several decades to indicate public dissatisfaction with the process of globalization on both sides of the political spectrum, from the 1999 WTO riots in Seattle, to the 2016 election of Donald Trump, the victory of Brexit, and the rise of Euroskeptic political parties. In spite of such events, globalization has been inexorable, and for good reason: in spite of its shortcomings, it has provided many benefits to the people of both developed and developing countries, and has helped lift billions of people out of dire poverty. But globalization means interconnection — and that means that while the condition of the Chinese economy didn’t matter much to American business in the 1980s, today it does.

The Main Drag in Shenzhen, China — in 1980 and today

Based on nominal GDP (that is, not adjusted for local prices), China now accounts for about 15% of the global economy, behind the U.S. at about 25% and the European Union at about 21%. A Chinese economic slowdown or contraction therefore matters to the global economy as much as a slowdown in the U.S., Europe, or Japan, and would have global ramifications. China’s financial system remains largely walled off from the global financial system, so a financial crisis in China would have limited direct effects on the rest of the world, and a lower risk of contagion than say, a banking crisis in Europe. But if a Chinese financial crisis led to a Chinese recession, the effects on the global economy would be more direct and severe. In the past ten years, China’s growth has represented between a quarter and a third of the world’s total growth.

What’s All This, Then?

This means that many global observers, from policy makers to central bankers to institutional investors, want to have an accurate picture of the current state of the Chinese economy and its trajectory.

Of course, they want to know these things about other systemically important global economies as well. The difference is that other economies — and especially the world’s major developed economies whose ranks China is aspiring to join — have abundant, largely transparent and easily available data that analysts can use to create a fairly accurate picture of reality.

When it comes to China, that simply isn’t the case. As we have pointed out for many years, official data from the Chinese government are notoriously unreliable. For example, one official data set purporting to measure the country’s unemployment rate has remained in a 3.5–4.5% band for the last 15 years. Many other basic macroeconomic statistics are obviously carefully managed. Often, data series will be revised or simply dropped if they begin to show trends that the government views as unfavorable. Under the pressure of the current trade conflict, of course, the government has an even greater motivation not to present data publicly that suggest the country is experiencing any kind of economic duress. That would weaken its bargaining position.

There are cultural expectations at work here as well. We can report anecdotally the experience of a major U.S. biopharmaceutical company that performed clinical testing at sites in both India and China. While the trial execution in India was sloppy by U.S. standards, auditors had confidence that it reflected the trial’s conduct accurately — in part because so many procedural lapses were documented and reported. In contrast, the trial record-keeping in China was pristine, leading to suspicions that errors were not documented and that compliance records probably omitted significant events (which are inevitable even in the best-run trials). In short, the Indian records presented a messy reality, while the Chinese records presented simply what the scientists thought their American counterparts would want to see. The data generated in the Chinese trial were ultimately excluded from U.S. regulatory filings.

Something not dissimilar is likely going on with officially reported Chinese data: present “what should be,” rather than “what is,” to save face for all concerned (ultimately, for the Communist Party, which is responsible for maintaining a strong and growing economy).

This reality has meant that a large industry has sprung up to derive more objective economic data for the People’s Republic. Sometimes those data are drawn from official statistics of China’s trading partners. Those more reliable data can be used to triangulate real numbers for Chinese manufacturing and export statistics and identify where the government is fudging numbers. Some go even further and resort to the analysis of satellite imagery, both visual and infrared. Satellite monitoring over time can show manufacturing and transport activity, the buildup and drawdown of inventories, and more. Modern telecommunications affords clever analysts a host of windows into the reality of Chinese economic activity unconstrained by the government’s public relations imperatives; search data from web giant Baidu [NYSE: BIDU] have been used as a proxy for consumer confidence and employment dynamics. (It remains to be seen how long those data will be available to analysts.)

What the data currently show is what you might expect from the concerns of the members of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai: deceleration. Some analysts have concluded that China’s GDP growth, for example, though still officially reported above 6%, may be closer to 3%. Manufacturing and industrial output are seeing significant slowdowns — much more severe than the official data indicate. Official statistics showed 5% industrial production growth in 2018 (already the lowest pace in nearly two decades), while privately generated data suggest that 2.5% is nearer the mark.

While challenged economics in China matter to foreign economies, businesses, and investors, they also matter to China’s leaders. We have often pointed out the basic bargain that comprises China’s authoritarian form of capitalism. The Party will engineer growth and keep lifting the masses our of poverty. In return, those masses will acquiesce to Party rule. If the Party slips in delivering on their end of the bargain, they know that public dissent could boil over, as it did at Tiananmen Square in 1989. Hundreds of millions of Chinese have joined the middle class — but hundreds of millions more are still waiting. Growth is an existential imperative.

The trade war is occurring at a period of economic distress for China, as the country slows from its massive, decades-long industrial boom and enters the dangerous waters of a transition to a consumer-led economy. Certainly, the U.S. administration knows that this is a tailwind for its own efforts to win concessions and improve Chinese trade behavior.

Investment implications: We continue to believe that both the U.S. and China are highly incentivized to make a deal resolving at least some of the elements of the current dispute. China’s economy is suffering more than the official data show and more than official spokespeople will admit. The U.S. is not under such duress, but the U.S. administration would benefit from the relief of getting a deal before the 2020 Presidential election. Chinese economic weakness suggests a deal is more, not less, likely.